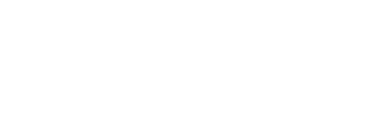

【海量案例】JiXXg v Minister for Immigration [2018] FCCA 8XX

ORDERS

(1) The application is dismissed.

FEDERAL CIRCUIT COURT

OF AUSTRALIA

AT SYDNEY

SYG 2XX7 of 2017

YUXXN JIXXG

Applicant

And

MINISTER FOR IMMIGRATION & BORDER PROTECTION

Respondent

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

Background

This is an application filed on 28 August 2017 seeking review of a decision of a delegate of the Respondent not to grant a criminal justice stay visa to the Applicant in these proceedings, Ms JiXXg. It is not in dispute that this court has jurisdiction to review such decision on the application of Ms JiXXg.

The decision not to grant a criminal justice stay visa to Ms JiXXg was made on 13 July 2017. These proceedings were not commenced until 28 August 2017. Hence Ms JiXXg required an extension of time under s.477 of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (the Act). I granted the extension of time. The delay was not extensive and was largely explained by the fact that Ms JiXXg did not become aware of the decision not to grant her a visa until some time after the decision was made and the fact that the initial attempt by her lawyer to file the application was unsuccessful, as the correct form was not used. Counsel for the Respondent submitted that the only factor that weighed against the grant of an extension of time was the lack of merit in the case. There was no claim that an extension of time would cause prejudice to the Respondent.

Having regard to the need to adopt a reasonably impressionistic approach to the consideration of merit (in the sense considered by Mortimer J in MZABP v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2015] FCA 1391; (2015) 242 FCR 585, upheld on appeal in MZABP v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2016] FCAFC 110; (2016) 152 ALD 478) I was satisfied that the Applicant’s case was not plainly hopeless and that there was some prospect of success. I bore in mind that one of the issues the Applicant wished to raise involved a contention of a failure to afford her natural justice. The Respondent submitted that such ground could not succeed in light of the decision of the Full Court of the Federal Court in Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v Zhang [2009] FCAFC 129; (2009) 179 FCR 135, which I was bound to follow. It appeared that the Applicant may have wished to submit formally that Zhang was wrongly decided, so that such issue could be reconsidered by the Federal Court were she to be unsuccessful and the matter go on appeal. I was conscious that there is no appeal from a decision refusing an extension of time (albeit that judicial review is available). In all the circumstances I considered it was necessary in the interests of the administration of justice to grant the extension of time and, as had previously been foreshadowed, to proceed with the hearing of the review application.

For the reasons that follow I am not satisfied that jurisdictional error has been established. The application should be dismissed.

Ms JiXXg is a citizen of China who arrived in Australia on 7 April 2017 as the holder of a visitor visa. On 12 April 2017 she (along with 5 other Chinese nationals who arrived in Australia on the same flight from China) was charged by the Western Australian police with demanding property by threats with intent to extort or gain. She was remanded in custody.

As a consequence of Ms JiXXg’s arrest her visitor visa was cancelled. She did not seek review of that decision. It is not the subject of these proceedings.

On 12 May 2017 Ms JiXXg was granted bail by a Western Australian Magistrates Court subject to specified bail conditions. However, as an unlawful non-citizen she was taken into immigration detention, where she remains.

On 29 May 2017 Ms JiXXg’s solicitors (who act for her in the present proceedings as well as in the criminal matter) emailed the Western Australian Commissioner of Police making a formal request regarding what was described as “the progress of the Criminal Justice Stay Certificate” for Ms JiXXg. They also indicated that they had asked the police officer in charge of Ms JiXXg’s case that “the application for a Criminal Justice Visa be commenced” for her.

On or about 31 May 2017 the Western Australian police asked the Director of Public Prosecutions for Western Australia (the DPP) to give a criminal justice stay certificate in relation to Ms JiXXg so that she could stay in Australia temporarily to face prosecution, trial and any subsequent sentencing.

On 6 July 2017 the DPP gave a criminal justice stay certificate (the certificate) under s.148 of the Act and also provided an undertaking to meet the cost of keeping Ms JiXXg in Australia while the certificate was in force and she did not have means of support. This had the effect of staying her removal or deportation from Australia. On the same day the DPP notified the Secretary of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection that the certificate had been given and requested the grant of a criminal justice stay visa.

On 13 July 2017 a delegate of the Minister made the decision not to grant a criminal justice stay visa to Ms JiXXg.

The legislative framework

Part 2 of the Act deals with the arrival, presence and departure of persons. Division 3 of Part 2 is headed “Visas for Non-Citizens”.

Usually, and subject to the Act, a non-citizen who wants a visa must apply for a visa of a particular class. Subdivision AA of Division 3 of Part 2 deals with applications for visas. As French J (as he was then) pointed out in Goldie v Commonwealth of Australia [2002] FCA 261 at [33] the provisions in Subdivision AA establish a “comprehensive procedure” for visa applications by non-citizens. However, s.44 provides that that subdivision and the later subdivisions of Division 3 of Part 2 (other than s.44, Subdivision AG and s.138(1)) do not apply to criminal justice visas. Subdivision AG and s.138(1) are of no relevance in this case.

What s.44 means is that the provisions of Division 3 of Part 2 which deal with applications for visas and the code of procedure for dealing with such applications do not apply to criminal justice visas (see Zhang at [14]). Hence the statutory provisions in relation to matters such as a valid visa application, who may make such an application, the Minister’s obligation to consider a valid visa application and, relevantly, the code of procedure for dealing fairly, efficiently and quickly with visa applications in Subdivision AB of Division 3 do not apply in relation to a criminal justice visa. Nor does Subdivision AC, which includes provisions in relation to decisions to grant or refuse to grant visas and notification of such decisions (see ss.65-69). In particular, the requirements of s.66 in relation to notification to an “applicant” of a decision to grant or refuse a visa and of s.67 (which specifies that a decision to grant or to refuse to grant a visa is taken to be made by the Minister causing a record to be made) do not apply to a decision to grant or refuse a criminal justice visa. Rather, as stated in s.38 of the Act, there is a class of temporary visas “to be known as criminal justice visas, to be granted under Subdivision D of Division 4” of Part 2.

Division 4 of Part 2 of the Act is headed “Criminal Justice Visitors”. As explained in s.141 of the Act, this Division was enacted “so that, if the administration of criminal justice requires the presence in Australia of a non-citizen, that non-citizen may be brought to, or allowed to stay in, Australia for the purposes of that administration.”

Under s.142, a criminal justice stay visa has the meaning given by s.155 of the Act. Subdivision C of Division 4 of Part 2 of the Act makes provision for criminal justice stay certificates to be given by an authorised official (see s.148). While a criminal justice stay certificate is in force, the person to whom it relates is not to be removed or deported from Australia (s.150). As indicated, the DPP gave such a certificate in relation to Ms JiXXg. However, in the absence of a criminal justice stay visa, she remains in immigration detention as an unlawful non-citizen, pending her trial and any sentence of imprisonment (see s.152 and Zhang at [32]).

As French J stated in Goldie at [36], “[t]hese provisions are enacted in the public interest in the administration of criminal justice. They are, on the face of it, not intended to create any rights or privileges on the part of the unlawful non-citizen. Of themselves they do not operate to displace the requirement that an unlawful non-citizen be detained (s189).”

Subdivision D of Division 4 of Part 2 deals with criminal justice visas. A criminal justice stay visa, if granted, permits a non-citizen to remain temporarily in Australia (s.155). A criminal justice entry visa permits a non-citizen to travel to, enter and remain temporarily in Australia (see ss.155-156). As Ms JiXXg is in Australia the relevant criminal justice visa is a criminal justice stay visa.

Section 157 provides that:

A criterion for a criminal justice stay visa for a non-citizen is that either:

(a) a criminal justice stay certificate about the non-citizen is in force; or

(b) a criminal justice stay warrant about the non-citizen is in force.

Section 158 is headed “Criteria for criminal justice visas” and is as follows:

The criteria for a criminal justice visa for a non-citizen are, and only are:

(a) the criterion required by section 156 or 157; and

(b) the criterion that the Minister, having had regard to:

(i) the safety of individuals and people generally; and

(ii) in the case of a criminal justice entry visa, arrangements to ensure that if the non-citizen enters Australia, the non-citizen can be removed; and

(iii) any other matters that the Minister considers relevant;

has decided, in the Minister's absolute discretion, that it is appropriate for the visa to be granted.

Section 159 addresses the procedure for “obtaining” a criminal justice visa. Relevantly, it is as follows:

(1) If a criminal justice certificate...in relation to a non-citizen is in force, the Minister may consider the grant of a criminal justice visa for the non-citizen.

(2) If the Minister, after considering the grant of a criminal justice visa for a non-citizen, is satisfied that the criteria for it have been met, the Minister may, in his or her absolute discretion:

(a) grant it by causing a record of it to be made; and

(b) give such evidence of it as the Minister considers appropriate.

If a criminal justice visa is granted the holder ceases to be an unlawful non-citizen. Such a visa gives the holder permission to remain in Australia while it is in effect and also entitles the holder to be released from immigration detention (s.161(1) and (2)(b)). However a criminal justice visa does not prevent the holder leaving Australia (see s.161(3)).

Subdivision E of Division 4 of Part 2 of the Act makes provision for the cancellation of criminal justice certificates (s.162) and for the consequential cancellation of any criminal justice visa that has been granted (s.164).

The decision

On 13 July 2017 a delegate of the Minister decided not to grant a criminal justice stay visa to Ms JiXXg. This is evidenced by material in the courtbook, in particular a document described as a “Minute” from the Community Protection Division of the then Department of Immigration and Border Protection to a delegate referred to by a position number. The Minute was prepared to “request” that the delegate consider granting a criminal justice stay visa to Ms JiXXg. The Minute referred to the background and the “issues” and recommended that the delegate consider exercising his or her delegation under the Act to grant or refuse a criminal justice stay visa to Ms JiXXg and “note” this decision on the Minute (cf s.159(2) of the Act).

The Minute described Ms JiXXg’s immigration history, her first and only entry into Australia on 7 April 2017 and the cancellation of her visa on 12 May 2017. It provided details of the circumstances of the alleged offence and of her co-accused who had also been charged and had their visas cancelled. The Minute recorded that Ms JiXXg was granted bail on 12 May 2017, but that she was taken from remand to immigration detention. It explained that the likely duration of Ms JiXXg’s stay in Australia depended on when a trial hearing date was set, the length of the trial and any subsequent sentencing hearings and that if Ms JiXXg was found guilty the maximum penalty for the offence was a term of imprisonment of 14 years.

The Minute attached a copy of the request for a criminal justice certificate that had been provided by the Western Australian Police to the DPP and the police factsheet.

The Minute advised the delegate of the criteria for a criminal justice stay visa and of the fact that the discretion to grant such a visa was set out in s.159 of the Act. The delegate was informed that in considering whether to exercise his or her delegation to grant Ms JiXXg a criminal justice stay visa he or she was required to take into account the criteria in ss.157 and 158, which were summarised.

The printed form of Minute allows the delegate to circle either that a criterion was “met” or “not met”.

The s.157 and s.158(a) requirement that a criminal justice stay certificate is in force was circled “Criterion met”.

In relation to the criterion in s.158(b) (set out above) the Minute drew the delegate’s attention (under the heading “the safety of individuals and people generally”) to the fact that the Western Australian police had listed “the following reasons why they believe that Ms JIXXG and her co-accuseds (sic) should not be granted CJSVs and allowed to enter the community”. It then referred to what was said to be the statement of a named detective, which was as follows:

I believe there is a serious threat to the community and to an individual regarding the six Chinese Nationals charged with Extortion (Demanding Property by Oral Threats Criminal Code, S397 (2)), on 12/April/2017.

The group of Chinese Nationals were financially funded by [a named person referred to for present purposes as G] to fly to Australia;

The group of Chinese Nationals (Charged persons) have made direct threats to kill the victim and have threatened his family;

The group of Chinese Nationals (Charged persons) have stated they can get other persons with guns to carry out the threats;

The group of Chinese Nationals (Charged persons) have had their passports seized by police however, it is believed with the financial backing of [G] that they would be able to source false passports and flee Western Australia;

If released on bail it is believed that the accused persons will carry out their threats to kill, harm or endanger the life of the victim, his family and employee’s (sic);

If released on bail the accused persons will attempt to influence prosecution witnesses to withdraw their statements and influence the Judicial Process.

The group of Chinese Nationals (Charged persons) located and attended the home address of the complainant and another family members (sic) (Brother and co – owner of [named business].)

The offence carries a maximum term of imprisonment of 14 years.

(emphasis in original)

The Minute also advised the delegate that the DPP had advised that “they [were] not aware whether Ms JIXXG had ever evaded criminal justice processes before” or of any medical conditions she may have.

The criterion in s.158(b)(i) was circled “not met”.

The Minute recorded that the criterion in s.158(b)(ii) was not applicable.

Under the heading “any other matters that the Minister considers relevant” the Minute explained that Ms JiXXg had been listed on CMAL following her visa cancellation and that an alert had been updated to reflect the issue of a criminal justice stay certificate and the charges she was facing. It recorded that there was no match for Ms JiXXg in “Risk Check” records, that it was not known if she had any family residing in Australia and that the DPP had signed a cost undertaking agreeing to meet the cost of keeping her in Australia.

This criterion was also marked “not met”.

The form is marked that the visa has been “REFUSED”. The Minute records the delegate’s position number and the date of 13 July 2017. The following hand-written “Comments” have been inserted at the end of the Minute:

Ms JIXXG is part of a group who allegedly travelled to Australia for the sole purpose of threatening the victim in this case. The group allegedly attended both the victim’s home and work and threatened both the victim and his family. Authorities believe that if released on bail Ms JIXXG and the other members of the group would carry out their threats to kill, harm or endanger the victim and his family and employees. Criteria is not met, CJV refused.

Ms JiXXg’s solicitors contacted the Department on 1 August 2017 indicating that they had been informed by the Western Australia police that a criminal justice visa had been refused. They took issue with the fact that the Department had “failed to provide any reasons for her refusal”. They sought such reasons.

A departmental officer replied by email of 3 August 2017 summarising the basis for the delegate’s decision and advising of the availability of judicial review. She pointed out that the criteria did not involve the same “test” as a decision by a court to grant bail.

Ground 1

Ms JiXXg now relies on an amended application filed on 21 December 2017. It contains five grounds. Ground 1 is as follows:

The Respondent failed to take into consideration relevant matters pursuant to s 158(b)(i) and (iii) of the Migration Act 1958 and in particular:

(a) The fact that the applicant had been granted bail by the Magistrate’s Court of Western Australia in Armadale;

(b) The conditions of her bail;

(c) The strength of the prosecution case as against the Applicant; and

(d) Materials other than those provided by the law enforcement agencies.

Ms JiXXg’s solicitor conceded that it was not the Minister’s/delegate’s responsibility to investigate the entire matter or to have regard to all the evidence to be presented in a criminal trial, but submitted that “a minimal bit of common sense” must be exercised when considering the material put before the decision maker. It was contended that the delegate had failed to take into account certain relevant matters (as particularised) and that these were matters about which the delegate should have made inquiries. The Applicant’s solicitor submitted that “requisitions” for additional documents ought to have been made by the delegate, because there was “glaringly contradicting” information on the face of the documents before the delegate.

Before considering these contentions I note that there is no suggestion that the delegate was under a statutory duty to produce reasons in relation to a decision not to grant a criminal justice visa (cf s.159(2)(b)). Ms JiXXg placed reliance on the Minute and the annotations thereto. However, as French CJ, Bell, Keane and Gordon JJ stated in Plaintiff M64/2015 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2015] HCA 50; (2015) 258 CLR 173 at [25]:

It is well settled that in the context of administrative decision-making, the court is not astute to discern error in a statement by an administrative officer which was not, and was not intended to be, a statement of reasons for a decision that is a broad administrative evaluation rather than a judicial decision (Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs v Wu Shan Liang (1996) 185 CLR 259 at 271–272, 278, 282; [1996] HCA 6). It is possible that error of law on the part of the Delegate might be demonstrated by inference from what the Delegate said by way of explanation of his decision; but it must be borne in mind that the Delegate was not duty-bound to give reasons for his decision (Migration Act 1958 (Cth), s, 66(2)(c) and (3)), and so it is difficult to draw an inference that the decision has been attended by an error of law from what has not been said by the Delegate (Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v SZGUR [2011] HCA 1; (2011) 241 CLR 594 at 605–606 [31]–[33], 615–618 [66]–[73]; [2011] HCA 1). Further, “jurisdictional error may include ignoring relevant material in a way that affects the exercise of a power” (Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v SZJSS [2010] HCA 48; (2010) 243 CLR 164 at 175 [27]; [2010] HCA 48; see also Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs v Yusuf [2001] HCA 30; (2001) 206 CLR 323 at 351–352 [82]–[84]); but here the plaintiff does not show that relevant material was ignored simply by pointing out that it was not mentioned by the Delegate, who was not obliged to give comprehensive reasons for his decision.

(emphasis in original)

While these remarks were made in relation to a decision to which the provisions of s.66 of the Act applied, the general thrust of the observations is in point.

Further, while ground 1 asserts that there was a failure to take relevant considerations into account, as pointed out in submissions for the Minister, a failure to take into account a particular consideration will only amount to a legal error where the statute in question expressly or impliedly imposes a mandatory requirement that the particular consideration is to be taken into account (see Minister for Aboriginal Affairs v Peko-Wallsend Ltd [1986] HCA 40; (1986) 162 CLR 24). As Deane J stated in Sean Investments Pty Ltd v MacKellar [1981] FCA 191; (1981) 38 ALR 363 at 375:

...where relevant considerations are not specified, it is largely for the decision-maker, in the light of matters placed before him by the parties, to determine which matters he regards as relevant and the comparative importance to be accorded to matters which he so regards.

The operation of the criminal justice stay visa process was considered by French J in Goldie. While that case involved a refusal to grant a criminal justice visa, the decision to refuse the grant of such visa was not directly impugned. At that time, a decision in relation to a criminal justice visa was excluded from the definition of “judicially reviewable decision” under s.475(2)(a) of the Act. French J pointed out (at [46]) that the Federal Court lacked jurisdiction in that respect. Nonetheless, his Honour’s remarks in Goldie about the “process” and the scope of Subdivision D of Division 4 of Part 2 of the Act are in point.

As French J stated at [44]-[45]:

It is immediately apparent from the arrangement of the sections of the Migration Act relating to criminal justice stay visas that they do not attract the procedural requirements relating to visas generally. In particular, there is no provision for a person to apply for the grant of such a visa.

The criteria for the grant of a criminal justice stay visa specified in s 157 are alternative necessary conditions for the grant of such a visa in the sense that one or other of them must be satisfied before such a visa is granted. The satisfaction of either criterion does not establish an entitlement in the unlawful non-citizen to the issue of a criminal justice stay visa. Nor is there any statutory right to apply for one. Section 158 describes as the only additional criterion to that imposed by ss 156 and 157, that the Minister has decided, in his absolute discretion, that it is appropriate for the visa to be granted. There is, of course, no such thing as an absolute discretion in the literal sense. A statutory discretion must be exercised by reference to the subject matter, the scope and the purpose of the legislation which creates it - Water Conservation and Irrigation Commission (NSW) v Browning (1947) 74 CLR 492 at 505; R v Australian Broadcasting Tribunal Ex parte 2HD Pty Ltd (1979) 144 CLR 44 at 49; De L v Director-General NSW Department of Community Services (1996) 187 CLR 640 at 661. In this particular case it is required to be informed by considerations of public safety. The reference to an absolute discretion may be taken as a reference to the very wide range of matters the Minister may take into account and the intention of the legislature that his discretionary decision shall not lightly be reviewed.

While s.158 states in clear terms that it is a criterion that a criminal justice certificate be in force and specifies matters to which the decision-maker must have regard, it is then left to the “absolute discretion” of the decision-maker (in the sense considered in Goldie) to decide that it is appropriate for the visa to be granted. French J observed in Goldie at [46] that the criterion that the Minister has decided that the grant of the criminal justice visa “is appropriate” cannot be “satisfied” by a person who wishes to be granted such a visa. Rather, it is “an evaluative decision by the Minister, the existence of which is characterised as a condition of the grant for the purposes of the Act”.

The legislature has not prescribed the circumstances that the Minister/delegate may take into account as part of “any other matters” that he or she considers relevant. In Zhang at [40]-[41] the Full Court of the Federal Court pointed out that the criteria for a criminal justice visa are stated “exhaustively” in s.158 and “are, and only are” as stated there, and that s.159, which sets out the procedure for obtaining a criminal justice visa, makes no provision for an application by a prospective visa holder. Rather, it merely states that if a criminal justice certificate or stay warrant is in force the Minister may consider the grant of a criminal justice stay visa. The Full Court stated (at [42]) “[t]he scope of the Minister’s discretion is reiterated in s 159(2) which provides that, if the Minister is satisfied that the criteria have been met, he or she may grant the visa in the Minister’s “absolute discretion”.

Insofar as this ground (or any other ground relied on by Ms JiXXg) involves an assertion that she was the “applicant” for a criminal justice visa, as Goldie and Zhang make clear, that was not the case.

Sections 157 and 158 of the Act do set out criteria and matters to which regard is to be had, relevantly “the safety of individuals and people generally” and “any other matters that the Minister considers relevant”. The handwritten annotations to the Minute and the comments endorsed thereon reveal that these factors were addressed in the course of the delegate considering whether the visa should be granted. However, in the face of the plain language of s.158, in particular the fact that it is specifically stated that there are no criteria other than those listed therein, and having regard to the subject matter, scope and purpose of these provisions (see Goldie at [45]), there is no foundation for an assertion that the delegate was obliged, as a matter of law, to refer expressly to the specific matters referred to in the particulars to ground 1 in recording the decision not to grant the visa (and see s.159(2)(a)). It has not been established that the delegate failed to take into account a consideration that he or she was “bound” to take into account in the Peko-Wallsend sense.

In any event, I am not satisfied that it can be inferred that the delegate did not consider the fact that bail had been granted to Ms JiXXg as asserted in particular (a) to ground 1. The Minute referred to the grant of bail on 12 May 2017. The Minute also attached a copy of the request for a criminal justice certificate and the police factsheet that contained details of the case and relevant advice from the DPP. The fact that a magistrate had granted bail to Ms JiXXg did not mean that the delegate was required to grant the visa that would entitle her to be released from detention under s.161 of the Act. As the Respondent submitted, the determination of whether it was appropriate to grant a criminal justice stay visa, taking into account “the safety of individuals and people generally”, was within the absolute discretion of the decision-maker as stated in the concluding words to s.158 of the Act.

It was also asserted (in particular (b) to ground 1 in the amended application) that the Respondent erred in failing to take into account the “conditions” of Ms JiXXg’s bail. Section 158(b)(i) requires the decision-maker to have regard to “the safety of individuals and people generally”. This criterion was addressed in the Minute and in the annotations and comments. It is the case that there is no reference to the conditions of bail in the Minute or annotations thereto. However, for the reasons stated above, the specific bail conditions were not matters that the delegate was required to consider as mandatory relevant considerations. As the Respondent conceded, it would have been open to the delegate to have regard to a matter such as the conditions of bail, but beyond the requirement to have regard to the matters in ss.158(b)(i)-(iii), the Minister or delegate is effectively entitled to determine what matters he or she considers relevant. Contrary to the oral submission for Ms JiXXg, Goldie does not support her proposition in this respect.

The “strength of the prosecution case” against Ms JiXXg (particular 1(c)) is not a mandatory relevant consideration. As conceded for Ms JiXXg, there is no reason to infer that the delegate was required to conduct a review of all evidence against her in the criminal case to form a view on the strength of the prosecution case as part of the process of considering whether it was appropriate to grant a criminal justice stay visa. As suggested for the Respondent, it is unlikely that Parliament intended such a review to occur in circumstances where the Act provides no mechanism for evidence relevant to a prosecution to be provided to the Minister, beyond the need for evidence of the fact of a criminal justice certificate.

Ms JiXXg also submitted that the delegate should have considered “[m]aterials other than those provided by the law enforcement agencies” (particular 1(d)). The specific “materials” that it is said should have been considered were not particularised. In submissions the Applicant appeared to re-characterise ground 1 as a contention that the delegate should have made further inquiries or “requisitioned” further documents before making the decision, in circumstances where there was said to be “glaringly contradicting information” on the face of the documents before him or her. No authority was cited in support of this proposition.

In support of these contentions and grounds 2 and 3 Ms JiXXg’s solicitor drew the court’s attention to the questionnaire that formed part of the request for a criminal justice certificate that the Western Australian Police had completed for the Western Australian DPP. A copy of this questionnaire was provided to the Department and referred to in the Minute. It was submitted that there were contradictory statements of fact in the questionnaire that the delegate had failed to consider and that the questionnaire contained erroneous material and baseless allegations not supported by any evidence.

The Applicant pointed out that question 5 in the questionnaire was as follows:

To best (sic) of the requesting agency’s knowledge, has the a/n [which is a reference to the “above named”, being the person in relation to whom the criminal justice certificate is sought] ever evaded criminal justice processes or do you have any information that indicates that the a/n is likely to evade authorities? If yes, please give details.

The Western Australian police provided the following answer:

There are no instances known where the a/n has ever evaded criminal justice processes. The a/n has been charged with five co-offenders whom are alleged to have flown from China to extort a large sum of cash from the victim. It is believed that the a/n and five other Chinese Nationals will return to China as soon as released from incarceration.

Ms JiXXg submitted that the allegation that she and her co-accused would return to China as soon as they were released from incarceration was not relevant to “the question itself” and was also in stark contrast to the fact that there were no known instances where she had evaded criminal justice processes and to the disclosure (in response to question 4) that she had no known criminal history in Australia and that it was unknown whether she had a criminal history in any other country.

These contentions were relied on in support of the proposition that in the face of such “contradictory” information the delegate was under an obligation to make some inquiries.

The fact that the questionnaire was before the delegate is not such as to indicate that the decision-maker erred in any of the ways contended for by the Applicant, whether by having regard to any information therein, by failing to do so, or by failing to make inquiries. Given the breadth of the decision-maker’s power under s.158 and the “absolute discretion” in circumstances where there was no visa application made by the potential visa holder, it would be antithetical to the statutory scheme to impose a requirement on the Minister or delegate to conduct some further inquiry in the general and unspecified manner contended for by the Applicant. Ms JiXXg did not identify a particular inquiry that should have been made or particular information that should have been obtained by the delegate in relation to the issues said to be raised by this part of the questionnaire.

Moreover, if the suggestion by the police that it was “believed” that Ms JiXXg and 5 other Chinese nationals would return to China as soon as released from incarceration was in some way “irrelevant” to the decision in relation to the criminal justice stay visa, it is difficult to see how a failure to take into account such an irrelevant matter could amount to a jurisdictional error. Nor is there any necessary contradiction in what was said in response to questions 4 and 5 in the questionnaire, given that Ms JiXXg had only been in Australia for such a brief time.

Ms JiXXg also asserted that an issue was raised by question and answer number 7 in the questionnaire. The question was as follows:

Do you consider that the presence of the a/n in Australia represents a danger to individuals and people in general? If yes, why?

The response from the police in the context of requesting a criminal justice certificate was as follows:

The a/n has been charged with five co-offenders whom are alleged to have flown from China to extort a large sum of cash from the victim. It is believed that the a/n and five other Chinese Nationals are a threat to the victim/victim’s family in this matter only.

Ms JiXXg submitted that the answer to question 7, although relevant, was unsupported by any evidence or circumstantial facts other than the charge itself, which she denied. It was submitted that she ought to have been given the benefit of the doubt that she was innocent until proven otherwise.

It is not clear how such assertions are said to support the proposition that the delegate failed to take into account relevant considerations or should have made inquiries. It is clear that the delegate was made aware that Ms JiXXg was facing charges of a particular nature, but that she had not yet been tried. There was evidence before the delegate in this respect. The extent of the “threat” the police believed existed was explained in the answer to question 7. There was no suggestion of a threat to persons outside the victim/victim’s family. The Applicant has not explained what inquiries it is suggested the delegate should have made beyond the matters particularised, which are considered above. I am not satisfied that in failing in some way to deal expressly with this aspect of the evidence the delegate can be said to have failed to take into account either a mandatory relevant consideration or an item of evidence in a manner constituting jurisdictional error (for example in the sense considered in Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v SZRKT [2013] FCA 317; (2013) 212 FCR 99 and Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZSRS [2014] FCAFC 16; (2014) 309 ALR 67) or to have fallen into error of the nature considered in Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v SZIAI [2009] HCA 39; (2009) 111 ALD 15. There was no assertion of legal unreasonableness.

Written submissions for Ms JiXXg also drew attention to question 8 in the questionnaire and the police response. The question was as follows:

If the a/n is a defendant, will he/she be kept in police custody or remand until hearing / sentencing? If yes, where?

The response was:

The a/n was granted bail by the Armadale Magistrates Court on Friday 12 May 2017. The a/n is currently held at the Melaleuca Remand Facility awaiting release on bail. The a/n Tourist Visa has been cancelled and will be taken into Immigration Custody immediately upon release.

Ms JiXXg’s contention in relation to this aspect of the evidence appeared to be to the effect that the fact that she was granted bail by a Western Australian Magistrates Court meant that it could be inferred that the magistrate was satisfied that any risk of interference with witnesses or the community had been mitigated by the conditions imposed on her bail. It was submitted that the delegate should have turned his or her mind to what was said to be the fact that if such a person was a danger to society or to any individual or was at risk of absconding upon release then the magistrate would not have made the decision to release such person on bail. Ms JiXXg contended that in these circumstances the delegate ought to have made some inquiries.

However, as indicated above, it was open to the delegate to form his or her own view as to the appropriateness of the grant of a criminal justice visa, notwithstanding that in the different context of a bail application a magistrate had determined that the risk was sufficiently low that Ms JiXXg need not be held on remand. As indicated, it would also have been open to the delegate to have had regard to the fact of bail and any bail conditions, but the absence of any express reference to such matters in the “comments” endorsed on the Minute is not such as to establish that the decision-maker failed to have regard to such matters in a manner constituting jurisdictional error. Nor does it support the contention that the delegate erred in failing to make some (unspecified) inquiry.

Associated with the concern about question 8, Ms JiXXg expressed concern about question 9 and the response. Question 9 asked:

Is the a/n in the community subject to bail conditions? If so, what are the conditions and is the a/n complying with these conditions?

Issue was taken with the fact that the police response to this question was “No”. The Applicant contended that this answer was factually incorrect because bail conditions were in fact imposed. However, as the Respondent submitted, on a proper reading the answer was not incorrect. The first question asked was whether the Applicant was in the community subject to bail conditions. She was not in the community. Hence the second question, as to the nature of conditions and the Applicant’s compliance with such conditions, did not arise.

In any event, even if there was some ambiguity in this response, the Applicant has not explained how this would go to show jurisdictional error on the part of the delegate. The request for a criminal justice certificate was not a document prepared by the Minister or his delegate. It was not prepared for the Minister or for the delegate, but rather for the Western Australian DPP. The Minister’s delegate did not adopt its reasoning in this regard. A factual ambiguity in such material, even taken at its highest, would not undermine in a jurisdictional sense the decision of the delegate. This is not a case in which it can be said that the delegate made a legal or factual error or mischaracterised the evidence.

As submitted for the Respondent, even if the delegate did rely on such allegedly “erroneous” information, such reliance would not in itself establish error. There is nothing in the circumstances of this case to suggest (let alone establish) any fraud operating to stultify an essential step in the statutory scheme (cf SZFDE v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship [2007] HCA 35; (2007) 232 CLR 189 at [53]). Even if, contrary to my view, there was factually inaccurate material before the delegate, it has not been established that the delegate erred in a manner that involved any misunderstanding or misconception as to the criteria for a criminal justice visa in this case or that meant that the delegate constructively failed to exercise his or her jurisdiction.

Further, contrary to the Applicant’s oral submissions, the delegate was under no general duty to make inquiries, to locate information or to request additional documents that might bear upon his or her decision, whether in the sense considered in SZIAI at [25] or otherwise.

If the principles in SZIAI were to be regarded as applicable in the context of a consideration of whether to grant a criminal justice visa (a matter that was not addressed by Ms JiXXg), she has not established that there was a “critical fact, the existence of which is easily ascertained” (see SZIAI at [25]) that ought to have been inquired into by the delegate. Nor has it been established that the delegate failed to make inquiries in a manner that established jurisdictional error on some other basis.

Ground 1 as pleaded and as addressed in submissions is not made out.

Grounds 2 and 3

Ground 2 is that the Respondent “made the decision based on erroneous material provided by the Law Enforcement agency” although the solicitor for Ms JiXXg also characterised this ground (and ground 3) as an assertion that the delegate took irrelevant considerations into account.

Insofar as this ground relates to the content of paragraphs 4, 5, 7 or 8 in the questionnaire in the request for a criminal justice certificate completed by the Western Australian police it is discussed above. No jurisdictional error is established on that basis.

In submissions, the solicitor for Ms JiXXg also referred to an email from the detective who was the contact officer in the Western Australian police. The email of 1 June 2017 related to an attached request for criminal justice certificates for Ms JiXXg and her co-accused. It appears that it was sent to the Western Australian DPP who forwarded a copy to the Department of Immigration.

Ms JiXXg took issue with the fact that in addressing the issue of the safety of individuals and people generally, the Minute referred to the police having listed “the following reasons why they believe that Ms JIXXG and her co-accuseds (sic) should not be granted CJSVs and allowed to enter the community” and then quoted the information in this email explaining the officer’s belief that there was a serious threat to the community and to an individual.

It was contended by Ms JiXXg that the delegate had regard to this information (consistent with the comments endorsed on the Minute), but submitted that without any supporting or historical facts or other evidence supporting the police officer’s belief that there was a serious threat to the community and to an individual, this document should not have been taken into account in deciding whether or not to grant a criminal justice visa. It was submitted that it contained allegations that were not supported by evidence and were in stark contrast to the circumstantial facts disclosed in the questionnaire, that a number of allegations therein were erroneous and also that it failed to disclose the actual conduct said to have been engaged in by Ms JiXXg.

As indicated, even if some aspect of any of this material was erroneous and the delegate relied on erroneous information, this in itself would not establish jurisdictional error for the reasons given above. It has not been established that the delegate took into account any “irrelevant” consideration in the sense considered in Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs v Yusuf [2001] HCA 30; (2001) 206 CLR 323 at [69].

Concern about the views expressed in the email of 1 June 2017 quoted in the Minute was also said to be the basis for ground 3 in the amended application which is that “[t]he Respondent took into consideration baseless allegations that is (sic) not supported by any form of evidence”.

The Applicant’s complaints in this respect and also her concerns that the decision-maker should not have relied on comments by the police to the effect that there was a risk that she would return to China if released, as well as that she presented a risk to the victim and his family, do not establish legal error. The issue in the present context is not whether the contentions of the police were erroneous or not supported by evidence, but whether or not the delegate made a legal error, for example by making a finding that was not supported by any evidence or which was legally unreasonable. Insofar as ground 3 is intended to raise a “no evidence” ground it is not made out. The factual finding made by the delegate in the comments (noted on the Minute) was that “[a]uthorities believe that if released on bail Ms JIXXG and the other members of the group would carry out their threats to kill, harm or endanger the victim and his family and employees”. There was plainly evidence to support the finding that the authorities believed these matters, given the expression of those views in the material before the delegate. The Applicant’s case was not presented in terms of legal unreasonableness.

The delegate was required to consider, relevantly, “the safety of individuals and people generally”. The opinion of the police was relevant to this issue and the delegate was entitled to take it into account without conducting further inquiries.

Indeed, even if it was necessary to consider whether there was a basis for the delegate to find that Ms JiXXg and her co-accused might harm the victim or his family or employees (contrary to the manner in which s.158(b) is drafted), there was such a basis in the very recent allegation that she had been involved in such threats to the victim and his family such as to justify the laying of charges, notwithstanding that such allegations had not been proven to a criminal standard. It was open to the delegate in assessing future risk (a necessarily speculative task) to consider the potential visa holder’s past conduct (see, albeit in a different context, Muggeridge v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2017] FCAFC 200; (2017) 351 ALR 153 at [36]). In this case the recent history provided a firm basis for the delegate to conclude that there was a risk that Ms JiXXg would carry out the threats that she had allegedly made.

Neither ground 2 or ground 3 is made out.

Ground 4

Ground 4 is as follows:

The Respondent failed to provide the Applicant an opportunity to comment on adverse material in relation to the grant of the Criminal Justice Visa contrary to s 57 of the Migration Act 1958 and/or an opportunity to provide further materials in support of a grant contrary to s 55 of the Migration Act 1958.

The short answer to this ground is that the provisions in ss.55 and 57 of the Act do not apply. Those sections are in Subdivision AB of Division 3 of Part 2 of the Act which, under s.44 of the Act, does not apply to criminal justice visas. As the Full Court of the Federal Court stated in Zhang at [14] “[t]he effect of s 44(1) of the Act is that the provisions of Div 3 which deal with applications for visas and the code of procedure for dealing with such applications do not apply to criminal justice visas”. More generally, French J made the point in Goldie at [44] that the sections of the Act relating to criminal justice visas do not attract the procedural requirements relating to visas generally. I also note that s.57 involves an obligation to give particulars of information to an “applicant”, that is, a visa applicant, whereas there is no provision for a potential visa holder to apply for a criminal justice visa (see Zhang at [41]). Ground 4 is not made out.

Ground 5

Ground 5 in the amended application is that “[t]he Respondent failed to afford the Applicant Natural Justice by way of an opportunity to be heard”.

In oral submissions the solicitor for Ms JiXXg suggested that while ground 5 was expressed in terms of an opportunity to be heard, he had intended to contend that the principles of natural justice ought to be applicable and that Ms JiXXg ought to have been given an opportunity to comment on the allegations “put” against her. No authority was cited in support of this proposition. Rather, it was simply suggested that there was no provision that excluded the operation of the natural justice hearing rule.

Insofar as the Respondent pointed to the approach taken by the Full Court of the Federal Court in Zhang (discussed below), the Applicant submitted, briefly, that the court was at liberty to depart from the approach taken in Zhang because that case dealt only with the issue of whether the rules of natural justice applied to the exercise of the power to cancel a criminal justice certificate under s.162 of the Act.

It is the case that, as conceded by the Respondent, the limits on the natural justice hearing rule in s.51A of the Act are of no application in this case. Section 51A, which is in Subdivision AB of Division 3 of Part 2, does not apply to criminal justice visas and does not answer the question of whether the rules of natural justice apply.

However, as the Respondent also pointed out, in Goldie French J not only suggested (at [36]) that the provisions in Division 4 of Part 2 of the Act in relation to criminal justice certificates were enacted in the public interest in the administration of criminal justice and “are, on the face of it, not intended to create any rights or privileges on the part of the unlawful non-citizen”, but also stated at [44] that “[i]t is immediately apparent from the arrangement of the sections of the Migration Act relating to criminal justice stay visas that they do not attract the procedural requirements relating to visas generally”. There is no provision in the Act for a potential visa holder to apply for the grant of such a visa and in that sense to become an applicant to whom natural justice, whether in the sense of a right to comment on adverse material or to be afforded a hearing, might be required to be afforded. While such remarks may be obiter, they are strongly persuasive.

In Andreola v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs [2002] FCA 728; (2002) 120 FCR 345 Gray J agreed (at [23]) with French J’s characterisation of the nature of the provisions in Division 4 of Part 2 of the Act. In Lee v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship [2008] FCA 1023; (2008) 171 FCR 38 Lindgren J expressed the view (at [15]) that “[s]imilar observations” to those of French J in Goldie at [36] in relation to ss.147 and 148 of the Act were applicable to s.151 of the Act (which relates to criminal justice stay warrants). In my view such general observations also apply to the provisions in relation to criminal justice visas.

Further, in Zhang the Full Court of the Federal Court relevantly found (at [96]):

In our view, it is plain from the language of Div 4 of Pt 2 of the Act, and from its subject matter, scope and content, that the rules of natural justice do not apply to the exercise of the power to cancel a criminal justice certificate under s 162(1) of the Act.

In Zhang the court was considering the cancellation of a criminal justice certificate under s.162 of the Act (not the grant of a criminal justice visa). Insofar as Ms JiXXg suggested that Zhang was “distinguishable” on this basis, the Full Court stated generally at [96] to [106]:

[96] In our view, it is plain from the language of Div 4 of Pt 2 of the Act, and from its subject matter, scope and content, that the rules of natural justice do not apply to the exercise of the power to cancel a criminal justice certificate under s 162(1) of the Act.

[97] The entire focus and object of Div 4 is to facilitate the administration of criminal justice by securing the temporary presence in Australia of persons who would not otherwise be permitted to enter or remain in Australia.

[98] As French J said in Goldie v Commonwealth of Australia [2002] FCA 261 at [36], the provisions of Div 4 which deal with the grant of a criminal justice certificate are enacted in the public interest in the administration of criminal justice. His Honour observed that they are:

on the face of it, not intended to create any rights or privileges on the part of the unlawful non-citizen.

[99] It is also apparent from the observations of French J about the criminal justice stay visa process, that the rules of natural justice are excluded at every stage of the decision-making process under Div 4. His Honour said at [44]:

It is immediately apparent from the arrangement of the sections of the Migration Act relating to criminal justice stay visas that they do not attract the procedural requirements relating to visas generally. In particular, there is no provision for a person to apply for the grant of such a visa.

[100] Similarly, there is no provision for a person whose presence is required in Australia to apply for the grant of a criminal justice certificate.

[101] The observations of French J in Goldie at [36] were followed by Gray J in Andreola v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs [2002] FCA 728; (2002) 120 FCR 345 at [23] and by Lindgren J in Lee v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship [2008] FCA 1023; (2008) 171 FCR 38 at [15].

[102] Lindgren J also observed at [9] that the references to investigation, prosecution and punishment in the definition of the “administration of criminal justice” in s 142 make it clear that the relevant perspective is that of the administrators of the criminal justice system.

[103] It follows from Lindgren J’s remarks that the relevant perspective for the exercise of the power to issue or cancel a criminal justice certificate is that of the administrators of the system, not that of the person whose interests may in a broad sense be thought to be affected by the decision: see Lindgren J at [9] and [20].

[104] In our view, the observations of French J in Goldie and Lindgren J in Lee are plainly correct and we adopt them. In Lindgren J’s words at [20], the perspective that permeates Div 4 is that of the administrators of the criminal justice system.

[105] With respect to the remarks of Merkel J in Wasfi, we disagree with his Honour’s conclusion that the rules of natural justice are not excluded by Div 4. The whole tenor of the Division is to repose the decision making process in the relevant decision maker in the interests of the administration of criminal justice. The person affected by the grant of a certificate or its cancellation has no personal interest in it and no right to be heard.

[106] Even if, contrary to the views we have expressed, there is to be found an obligation of procedural fairness, it could have no content. The scheme laid down in Div 4 is inconsistent with any right, entitlement or interest of a person such as Mr Zhang to be involved in the consideration of the question of whether he could or should give evidence in the relevant proceeding. (emphasis added)

It is notable that the Full Court clearly expressed the view (at [99]) that “the rules of natural justice are excluded at every stage of the decision-making process under Div 4”.

Having regard to the generality with which the Full Court expressed the view that the scheme laid down in Division 4 of Part 2 was inconsistent with any obligation of procedural fairness, such views are applicable to a decision as to whether to grant a criminal justice visa. I consider that I am bound to follow Goldie and Zhang and hence to find that the rules of natural justice do not apply in relation to a decision not to grant a person a criminal justice visa.

For the sake of completeness I note that even if I was not bound to follow Zhang, I would find it very strongly persuasive and I would follow it. Not only did the Full Court adopt the wide view expressed by French J in Goldie at [44] in accepting that “the rules of natural justice are excluded at every stage of the decision-making process under Div 4” (at [99]), but their Honours also pointed out that “the relevant perspective” under Division 4 was that of the administrators of the criminal justice system (see Lindgren J in Lee at [9] and [20] and Zhang at [102]-[104]). Further, if principles of procedural fairness do not attach to the cancellation of a visa, which has the immediate effect upon a person of becoming an unlawful non-citizen who is then required to be detained under s.189 of the Act, then there would seem to be no reason not to take the same approach in relation to the consideration as to whether to grant a criminal justice visa. There is no provision for a person to apply for the grant of such a visa. The decision not to grant such a visa would not destroy, defeat or prejudice a person’s existing legal status as an unlawful non-citizen such as to enliven a duty of procedural fairness on the principles considered in Wasfi v Commonwealth [1998] FCA 639; (1998) 83 FCR 16. The remarks of the Full Court in Zhang as to the “tenor”, subject matter, scope and content of Division 4 of Part 2 are equally applicable in the present context.

Accordingly ground 5 is not made out.

As none of the grounds relied on by the Applicant has been established the application must be dismissed.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and one (101) paragraphs are a true copy of the reasons for judgment of Judge Barnes

Associate:

Date: 10 April 2018

1300 91 66 77

1300 91 66 77

首页

首页