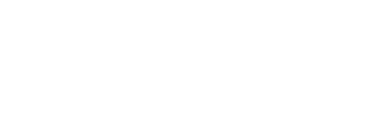

【海量案例】ZhXX v KoXXal & OXX [2012] VSC 1XX (63万元房屋1000元贱卖案)

HIS HONOUR:

Summary of Relevant Facts and Relief Sought

This action arises out of the purported sale of real estate by an auction conducted by the Second Defendant (“the Sheriff”) on 16 December 2010 (the “second auction”) pursuant to the Sheriff Act 2009 (the “Sheriff Act”).

The Plaintiff, Mr ZhXXXng ZhXX (“ZhXX”), is the registered proprietor of a property situated at X Wirraway Avenue, Braybrook (Certificate of Title Volume 10XX8 Folio 8X3) (the “Property”). He was born in Shanghai China on 16 February 1962. He immigrated to Australia in 1989 on a student visa following the 4 June 1989 uprising in Tiananmen Square in Beijing. He obtained permanent residency in Australia in 1993 and became an Australian citizen in 1998.

In Shanghai, ZhXX completed his studies at the Shanghai Mechanic Engineering University where he graduated with a Bachelor’s Degree in mechanical engineering. Since graduation and immigrating to Australia, he has worked principally in the area of building and construction.

ZhXX built a house on the Property himself, as the owner builder. Following completion of construction a Certificate of Occupancy was issued on 21 March 2006. The house is built of brick and has five bedrooms, and is a good house.

A warrant of seizure and sale No. AH030XX2M dated 9 November 2009 (the “Warrant”) was issued which commanded the Sheriff to seize and sell the Property.

At the time of the purported sale, ZhXX owed to the Fifth Defendant, Mr GuXX FeXX WX (“WX”), a judgment debt of over $100,000. The debt remained unpaid by ZhXX for almost three years and founded the issue of the Warrant. Wu took no part in the trial.

The Property was also subject to a mortgage in favour of the Fourth Defendant (“SunXXXX”).[1] The mortgage secured an amount then outstanding of approximately $457,345.50. SunXXXX took no part in the trial. The Property was also subject to a charge in the sum of $7,691.10 for Council rates.

[1] The Fourth Defendant (SunXXXX) is the mortgagee of the property pursuant to the mortgage registered over the Property on 12 June 2008, which bears the dealing number, AF90XXX1D.

The Third Defendant, the Registrar of Titles (the “Registrar”), likewise took no part in the trial and undertook to be bound by the result.

At the time of the auction, the Valuer-General for the State of Victoria valued the Property to be worth approximately $630,000.00 following a “kerbside” valuation. The valuation was supplied to the Sheriff prior to the purported sale.

At the second auction conducted by the Sheriff on 16 December 2010, the Property was knocked down to the First Defendant, Mr KoXXal (“KoXXal”) for $1,000.

It is this remarkable event which has given rise to the litigation.

ZhXX seeks a declaration that the Sheriff breached his legal duty by selling his interest in the Property at the Auction for an amount which was illusory, unfair, unreasonable in that it bore no relation to the evident worth of his interest in the Property, and he seeks an order that the purported sale be set aside. He also seeks damages against the Sheriff.

Against KoXXal, ZhXX seeks a declaration that he acted unconscionably in insisting upon his purported right to settle the contract of sale and register the transfer of the interest in his favour with Land Victoria.[2] ZhXX also seeks an order that the purported sale and transfer be set aside and that KoXXal be permanently restrained from lodging the transfer with the Registrar for registration.

[2] Formerly the Office of Titles.

Against the Registrar, ZhXX seeks an injunction permanently restraining him from the lodging the transfer for registration. No orders for costs are sought against the Registrar.

ZhXX seeks no orders against the mortgagee SunXXXX or the judgment creditor WX. These parties were joined to the proceeding because their interests may be affected by the outcome.

The parties have agreed that the assessment of damages should be heard separately by an Associate Justice, if that be necessary.

Background Factual Detail

ZhXX was and remains indebted to WX pursuant to a judgment entered in the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria on 12 March 2009 and in the Supreme Court of Victoria on 7 November 2009[3] (the “judgment debt”). The judgment remains unsatisfied.

[3] Proceeding S CI 2009 XXX92. As to whether the judgment is a judgment of the Magistrates’ Court or the Supreme Court, see Rushton v Braun (Unreported, Supreme Court of Victoria, Cummins J, 18 February 1997); Melville v Dartmouth Projects Pty Ltd (Unreported, Supreme Court of Victoria, Byrne J, 5 December 1997); O’Dea v The Magistrates’ Court of Victoria at Melbourne (Unreported, Supreme Court of Victoria, Gillard J, 20 July 1998); Michael JS Doyle & Associates (a firm) v Ornico Pty Ltd [2000] VSC 423 (Gillard J).

The judgment debt arose in the following circumstances. On or about 10 November 2008, WX commenced legal proceedings against ZhXX by way of Summons in the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria at Sunshine, claiming the amount of CNY440,000.00 (approximately AUD $96,660.00), being monies claimed to be outstanding and due to WX by ZhXX, arising from a loan agreement entered into between the two in about November 2006 (the “WX proceedings”).

The WX proceedings were served on ZhXX on or about 13 November 2008.

On 12 March 2009, the Magistrates’ Court at Sunshine entered judgment in the WX proceedings against ZhXX in favour of WX in the amount of AUD $96,660.00, together with interest in the amount of $5,487.11 and costs in the amount of $2,008.71, in all totalling AUD $104,155.82. The judgment was entered in default of ZhXX entering an appearance or defence.

On 7 October 2009, Wu obtained from the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria at Sunshine a certificate of judgment issued pursuant to s 112 of the Magistrates’ Court Act 1989 (Vic), with respect to the judgment debt (the “certificate of judgment”).

On 9 November 2009, in reliance upon the certificate of judgment, and upon the application of WX, the Supreme Court issued a Warrant of Seizure and Sale to be levied against the property of ZhXX.[4] This was served by the Sheriff upon ZhXX in early July 2010 (the “Warrant”).

[4] Warrant SW-09-XXX810-8 in proceeding S CI 2009 XXX92.

First Auction

A first public auction of the Property was conducted by the Sheriff on 15 July 2010.

Pursuant to the Warrant, the Sheriff sought to sell the Property by way of public auction, which was conducted at his offices located at 4XX Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria (the “first auction”).

At the time of the first auction the Sheriff had in his possession a property valuation prepared under the hand of the Valuer-General Victoria dated 28 June 2010. The valuation was stamped as received by the Sheriff’s Office on 5 July 2010. The property valuation fixed $630,000 as the value of the Property. The valuation relevantly provided as follows:

Further to your request dated 22nd June 2010, I have carried out a kerbside inspection of the subject property, examined comparable properties in the immediate area and provide the following details in regards to the estimated value of the subject property:

Description:

The property comprise[s] of a circa 2006 double storey brick veneer dwelling with a double attached garage.

Property Type Condition Car Accommodation Land Area Zoning

Dwelling Good Double Garage 396m2 Residential X Zone

Sales Evidence:

I advise that the following comparable properties have been considered in determining the estimated of value of the subject property: [here the details of 4 comparable properties are set out]

I BrXXXan SmXXX of WXX Property Group advise that I have made a Kerbside Inspection of the subject property on 28/06/2010 and assess the estimated market value at $630,000.

Signature:

Date: 28 June 2010

WXX PROPERTY GROUP

BRXXXAN SMXXX – AAP PATRICK J BRADY – AAPI, MRICS, Dip Ed

Certified Practicing Valuer 2XX0

Director

Certified Practicing Valuer 1XX7

Confirmation:

As requested a detailed inspection of the property has not been made. Therefore, this is not a fully informed opinion of value and should not be construed as a formal valuation made under the Valuation of Land Act 1960.

You are advised that the estimate of value is certified as meeting VGV standards. However, in the event of a forced sale, it is likely that the realised figure may not reach the amount indicated above.

ROBERT MARSH

Valuer-General.

At the time of the first auction there was $452,691.70 outstanding to the mortgagee SunXXXX and $5,692.54 owing to the MariXXXXXng City Council for arrears of rates charged to the Property. This left an equity for ZhXX in the sum of $171,615.76 which was set as the “Sheriff’s Reserve” for the Property, as recorded on his “Real Estate Auction Sheet” retained on the Sheriff’s file.

The first auction was conducted, however no bids were received by the Sheriff and the Property was passed in.

Orders of Mukhtar AsJ

On application by the Sheriff, orders were then made on 1 October 2010 by Mukhtar AsJ in proceeding S CI 2009 XXX92 (the “Order”) permitting the Sheriff to sell the Property without a reserve.

In the Order, Mukhtar AsJ in “Other Matters” and in paragraphs 1 and 3 relevantly noted and ordered as follows:

OTHER MATTERS:

1. There is evidence that the sheriff attempted to sell the subject property by auction on 15 July 2010, but the property was passed in without bid.

2. The execution creditor seeks an order allowing the Sheriff to attempt another sale by action of the recoverable property but without a reserve price. It is believed by the Sheriff (with whom the execution creditor has been dealing) that such orders have been made by the Court in the past.

3. There is no explicit power in the Rules or the Sheriff Act to grant such a permission. The Court’s power under Rule 66.15 “to make such an order as it thinks fit in the aid of enforcement of a warrant of execution” is made on the application of the Sheriff, not the execution creditor.

4. Presumably, such an order has been made on the exercise of the Court’s inherent jurisdiction over its own processes, including execution. But what prevails is the Sheriff’s duty when exercising a power of sale, which may well be satisfied even if a sale occurs without a reserve price.

5. An order of this nature should either be made by application on notice to the execution debtor, or, can be made on terms that require procedural service of this order on the debtor with an opportunity to discharge the order. It is convenient in the circumstances to do the latter.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Subject to paragraph 3 there be leave to the Sheriff to conduct a sale of the property known as X Wirraway Avenue, Braybrook (in exercise of powers under a warrant of seizure and sale filed 9 November 2009) without a reserve price provided that such leave does not thereby derogate from, or relieve the Sheriff of a duty at law to the owner of the land when exercising a power of sale.

2. ….

3. There be leave to the owner of the property to notify the Plaintiff of an intention to discharge the order in paragraph 1, and apply to this Court for a discharge of that order. Unless such an application is filed and served within 10 days after the date of the service of this order, the order will take effect upon the Plaintiff’s solicitor giving to the Sheriff evidence of service of this order and the absence of any application to discharge it.

4. ….

5. ….

It is important to note that, although the Order of Mukhtar AsJ expressly authorised the Sheriff to conduct a sale of the Property without a reserve price, this was not an unfettered authority to sell at any price which could be obtained. The Order expressly directed that any such sale must be conducted in a manner which did not “derogate from, or relieve the Sheriff of a duty at law to the owner of the land when exercising a power of sale”.

ZhXX neither satisfied the judgment nor took any step to prevent the sale before it occurred.

Second Auction

A second public auction was conducted by the Sheriff at his offices on 16 December 2010 (the “second auction”).

At the time of the second auction the market value of the Property was accepted by the Sheriff as being approximately $630,000.00, founded on the Valuer-General’s earlier valuation, as shown on the “Real Estate Auction Sheet”. However, at the time of the second auction there was $457,345.50 outstanding to the mortgagee SunXXXX and $7,691.10 owing to the Maribyrnong City Council for arrears of rates charged to the Property. This left an equity for ZhXX in the sum of $164,963.40 which was set as the “Sheriff’s Reserve” for the Property as shown on his “Real Estate Auction Sheet”, except that the words “NO RESERVE” were also included beside the stated reserve, no doubt to reflect the Order of Mukhtar AsJ made 1 October 2010.

At the time of the second auction, the financial value of ZhXX’s interest in the Property was therefore approximately $165,000 ($630,000 ― $457,345.50 ― $7,691.10 = $164,963.40) (“ZhXX’s equity”).

The Sheriff offered the Property for sale at the second auction, without a reserve price.

The second auction was conducted at the Sheriff’s premises at 4XX Swanston Street, Carlton, by the real property sales officer of the Sheriff, Mr KeXXXX GrXXXXn. The auction was overseen by another officer of the Sheriff. Two potential bidders attended the second auction, namely the ultimate purchaser KoXXal, and one other person.

KoXXal was an experienced purchaser of property at public auctions conducted by the Sheriff. Every Thursday or soon thereafter, he was accustomed to review the Government Gazette to search for advertised Sheriff auctions of land. One week or so before the auction day, he would enquire at the Sheriff’s Office as to whether the advertised auction was scheduled to proceed. If so, he would assess the land, its value, encumbrances, money owed on the property and he would set himself a budget for the purchase. Prior to the auction in issue in this proceeding, KoXXal had previously bought land from the Sheriff and had attended seven or eight unreserved Sheriff auctions.

Prior to the second auction, KoXXal had never met or had any dealings with either ZhXX or WX, and knew nothing at all of their personal, social or financial circumstances.

The second auction proceeded on 16 December 2010 as follows. After reading aloud the Government Gazette advertisement for the sale of the property and the terms of the auction, Mr GrXXXXn advised the attendees that $457,345.50 was owed to SunXXXX under a registered mortgage on the Property and that $7,691.10 was owed to the Maribyrnong Council for arrears on rates. He invited bids for ZhXX’s remaining interest in the Property. KoXXal bid $100. Another bidder bid $200. KoXXal then bid $1,000. There being no further bids, Mr GrXXXXn knocked the Property down to KoXXal.

Immediately following the second auction KoXXal paid Mr GrXXXXn the $1,000 and received a receipt and a copy of the transfer. Mr GrXXXXn later sent KoXXal a copy of the transfer of the Property signed on behalf of the Sheriff.

Subsequent Events

On the 21 December 2010, KoXXal wrote to ZhXX and asked him his intentions in relation to remaining in possession of the Property. He received no reply. On or about the 5 January 2011, KoXXal was present during a phone call between a Mandarin Chinese speaking interpreter and ZhXX. KoXXal instructed the interpreter to advise ZhXX that he had bought the property from the Sheriff and instructed him to ask ZhXX what his intentions were. The interpreter told KoXXal that ZhXX didn’t want anything to do with him and that he should leave him alone.

By Summons dated 11 May 2011, KoXXal commenced legal proceedings against SunXXXX seeking orders pursuant to s 116(3)(a) of the Transfer of Land Act 1958 (Vic) (the “Transfer of Land Act”) that it deliver up the duplicate Certificate of Title for the Property, so that KoXXal could register his interest in the Property with the Registrar of Titles.

On 30 June 2011, KoXXal obtained orders that SunXXXX

“produce the duplicate Certificate of Title [for the Property] to the [the Registrar of Titles] for the purpose of enabling [KoXXal] as transferee to lodge a transfer of that land from the [Sheriff] as transferor under the [Warrant]”.

On 15 July 2011, ZhXX in the present proceedings, by Amended Summons on an Originating Motion dated 13 July 2011, sought and obtained orders from the Court that:

(a) “Until further Order, the Third Defendant [Registrar of Titles] be restrained from registering any transfer of the property ... from the Plaintiff [ZhXX] and/or Second Defendant [the Sheriff] to the First Defendant [KoXXal], executed as a consequence of the sale of the Property which was effected on or about 16 December 2010; and

(b) Until further Order, the Third Defendant [Registrar of Titles] be restrained from registering any other interest in the Property”.

Pleadings

By his Amended Statement of Claim, ZhXX pleads that in conducting the second auction, the Sheriff at all material times was under a legal duty to:

(a) to act reasonably in his interests in executing the Warrant; and/or

(b) to obtain a fair price for the interest being sold under the Warrant; and/or

(c) not to accept any bid, which was illusory, unfair, unreasonable, or bore no relation to the evident worth of the land or interest being offered;

and that these duties had been breached, resulting in the purported sale being liable to be set aside, alternatively giving rise to a liability for the Sheriff to pay damages.

It is further pleaded against KoXXal that, at all material times prior to and up until the time of the purported sale, he knew that the property was not being sold by the Sheriff voluntarily, but rather involuntarily and/or under duress, by the Sheriff (for and on behalf of Wu and ZhXX), and that KoXXal knew or ought to have known that his bid at $1,000 was:

(a) illusory; and/or

(b) unfair; and/or

(c) unreasonable; and/or

(d) bore no relation to the evident worth of ZhXX’s interest in the land being offered;

consequently, it is pleaded, the purported sale is unconscionable in equity and ought be set aside.

It is further pleaded that the consideration paid by the KoXXal to the Sheriff to support the purported sale, namely $1,000, is not a proper or valuable consideration within the meaning of s 52 of the Transfer of Land Act, and because the purported sale is not supported by proper or valuable consideration within the meaning of s 52 of the Transfer of Land Act, KoXXal is not properly entitled to registration of the transfer by the Registrar of Titles.

At the commencement of the trial the Court raised with counsel a question as to whether a writ of certiorari was also open to be argued on the grounds of jurisdictional error on the part of the Sheriff and his office on any of the following grounds, or possibly other grounds:

(a) Failing to take into account any relevant considerations, or taking into account irrelevant considerations?

(b) Bad faith?

(c) Unfairness amounting to an abuse of power?

(d) Wednesbury unreasonableness?[5]

[5] Associated Provincial Picture Houses Ltd. v Wednesbury Corporation [1947] 1 KB 223

If the facts as pleaded by ZhXX had been established, I have no doubt that such grounds would have been open to have been argued.[6] The Sheriff and his office are amenable to certiorari if the proper grounds are made out because in exercising coercive power in the course of conducting sales of property under the Sheriff Act administrative decisions are made which, at the very least, amount to a step in a process which is capable of altering the rights and interests of the original owner of the property sold.[7]

[6] R v Electricity Commissioners; Ex parte London Electricity Joint Committee Co (1920) Ltd [1924] 1 KB 171 at 205; Ridge v Baldwin [1964] AC 40 at 74-76; Banks v Transport Regulation Board (Vic) (1968) 119 CLR 222 at 233-234; Craig v State of South Australia (1995) 184 CLR 163 at 175-176 (“Craig”); Re McBain: Ex parte Australian Catholic Bishops Conference (2002) 209 CLR 372; Byrne v Marles [2007] VSC 63 at [65] per Kaye J; Grocon Constructors v Planit Cocciardi Joint Venture (No.2) [2009] VSC 426 at [39]-[48] per Vickery J; Kirk v Industrial Relations Commission (NSW) and Anor (2010) 262 ALR 569 (“Kirk”); Associated Picture Houses Ltd v Wednesbury Corporation [1948] 1 KB 223 at 631–632; Minister for Immigration v Bhardwaj (2002) 209 CLR 597 at 616 [53].

[7] See: Ainsworth v Criminal Justice Commission (1992) 175 CLR 564 at 580; Hot Holdings Pty Ltd v Creasy (1996) 134 ALR 469 at 475–476 in the joint judgment of Brennan CJ, Gaudron and Gummow JJ.

However, counsel did not seek to amend the pleadings to incorporate any administrative law remedies, and the matter proceeded to trial in their absence.

The Case Against KoXXal

It was alleged by ZhXX that the purported sale was and is unconscionable in equity and ought be set aside as against KoXXal.

Although there are various grounds on which equity may intervene to refuse enforcement of or to set aside transactions which offend its principles, the present litigation was conducted on the well established equitable principle that a transaction may be set aside where unconscientious advantage was alleged to be have been taken by one party of the disabling condition or circumstances of the other. In such cases, equity may intervene either because the will of the complainant is overborne so that it is not independent and voluntary or when advantage is taken of an innocent party who is unable to make a worthwhile judgment as to what is in his or her best interests.

The origin of this doctrine in Australia may be traced back by statements made by the High Court in Blomley v Ryan. [8]

[8] Ibid at 415.

In Blomley v. Ryan, Kitto J observed:

The court has power to set aside a transaction. Whenever one party to a transaction is at a special disadvantage in dealing with the other party because of illness, ignorance, inexperience, impaired faculties, financial need or other circumstances, affecting his ability to conserve his own interests and the other party unconscientiously takes advantage of the opportunity, thus placed in his hands.[9]

[9] Ibid at 415

In the same case, Fullagar J noted the circumstances adversely affecting a party which may induce a court of equity, either to refuse its aid or set a transaction aside, are of great variety and can hardly be satisfactorily classified. [10] Among them are poverty or the need of any kind, sickness, age, sex, infirmity of body or mind, drunkenness, illiteracy or lack of education, lack of assistance or explanation where assistance or explanation was necessary. The common characteristic is that they have the effect of placing one party at a serious disadvantage vis-à-vis, the other.

[10] Ibid at 405.

The more contemporary authority of Commercial Bank of Australia v Amadio, was relied upon by ZhXX. [11] Reference was made to the observations of Mason J where his Honour observed:

Relief on the ground of unconscionable conduct would be granted when unconscientious advantage is taken of an innocent party whose will is overborne so that it is not independent and voluntary, just as it will be granted when such advantage is taken of an innocent party who, though not deprived of an independent and voluntary will, is unable to make a worthwhile judgment as to what is in his best interest. [12]

[11] (1983) 151 CLR 447 (“Amadio”).

[12] Supra at 461.

Deane J expressed the following views in Amadio:

Unconscionable conduct exists in circumstances in which (1) a party to a transaction was under a special disability in dealing with the other party with the consequence that there was an absence of any reasonable degree of equality between them, (2) that disability was sufficiently evident to the stronger party to make it prima facie unfair or unconscientious that he procure or accept the weaker party's assent to the impugned transaction in circumstances in which he procured or accepted it.

Where such circumstances are known to have existed an onus is cast on the stronger party to show that the transaction was fair, just and reasonable. [13]

[13] Ibid at 474.

As observed by Gleeson CJ in ACCC v Berbatis Holdings P/L unconscientious exploitation of another’s inability, or diminished ability, to conserve his or her interests is not to be confused with taking advantage of a superior bargaining position. [14] It is only unconscientious exploitation of another’s inability, or diminished ability, to conserve his or her interests that is of legal consequence. His Honour explained further:

A person is not in a position of relevant disadvantage, constitutional, situational or otherwise, simply because of inequality of bargaining power. Many, perhaps even most, contracts are made between parties of unequal bargaining power, and good conscience does not require parties to contractual negotiations to forfeit their advantages, or neglect their own interests. [15]

[14] [2003] 214 CLR 51 at 64.

[15] Ibid at 64 [11].

In the present case it was at first apprehended by KoXXal that the special disability relied upon by ZhXX was his alleged difficulty with the English language. KoXXal made submissions on the point through his counsel, Mr HaXXXXon.

Depending on the circumstances of the case difficulty with language may amount to a special disadvantage.

However, I am far from satisfied that ZhXX suffered from any such special disability. Although he had difficulty with the English language to a degree, I am not satisfied that this deprived him of an independent and voluntary will, or gave rise to him being unable to make a worthwhile judgment as to what is in his best interests or that this gave rise to any relevant degree of inequality between the two parties.

ZhXX is tertiary-educated and spent five years at University in China resulting in an engineering degree. His occupation in Australia was an owner-builder. His property dealings in Australia may be summarised as follows:

Date Action Lawyer involved? Certificate of title

27 April 2000 Purchase Yes volume 10XX6 folio 13X

11 March 2003 Purchase Yes volume 10XX3 folio 25X

21 July 2003 Purchase unknown volume 10XX8 folio 85X

9 September 2004 Purchase volume 10XX4 folio 65X

16February 2005 Acquisition as a gift volume 10XX9 folio 03X

21 October 2008 Sale Yes volume 10XX4 folio 65X

5 October 2009 Sale Yes volume 10XX6 folio 13X

7 February 2011 Subdivision Yes volume 10XX3 folio 25X

27 July 2011 Sale unknown volume 10XX3 folio 25X

27 July 2011 Sale unknown volume 10XX3 folio 25X

27 July 2011 Sale unknown volume 10XX3 folio 25X

31 August 2011 Sale Yes volume 10XX9 folio 03X

Thus, from 2000 ZhXX has bought and sold property at least 10 times. Except for two occasions in 2004 and 2005, he engaged the services of a lawyer for the transaction. His alleged language difficulties have not prevented these property dealings; nor have they prevented him from earning substantial income in his dealings with land. ZhXX took his oath in English and answered some questions in evidence directly in English.

Further, even if ZhXX's difficulty with the English language was accepted as a special disability, there is no evidence that the First Defendant KoXXal knew of the disability or indeed took advantage of it in purchasing the property. Prior to the second auction he had never met ZhXX and was not aware of his social circumstances or his capacity to speak English. Accordingly, it is not possible to find on the evidence that ZhXX had any disability of the recognised kind that was sufficiently evident to KoXXal such as to make it prima facie unfair or unconscientious that ZhXX be compelled to proceed with the impugned transaction.

However, in the course of the application Mr HaXXX, who appeared on behalf of ZhXX, put the alleged special disability suffered by ZhXX upon on an entirely different basis. That is, by reason of the sale by the Sheriff being of a compulsory nature under the statute, and conducted under the provisions of the Sheriff Act, and being further conducted pursuant to the order of Mukhtar AsJ, which permitted, amongst other things, the sale to be conduced without a reserve, ZhXX was placed under a special disability in relation to the sale of his property.

This was a special disability which was submitted ought to be recognised by equity for the purposes of the doctrine of unconscionable conduct.

In ACCC v Samton Holdings Pty Ltd the Full Court described the relevant special disadvantage for the purposes of the equitable doctrine in two categories:

(a) special disadvantage which is constitutional: that is, deriving from age, illness, poverty, inexperience, lack of education or some other such circumstances peculiar to the complainant; or

(b) special disadvantage which is situational: that is, deriving from particular features of a relationship between actors in the transaction such as emotional dependence of one on the other. [16]

[16] (2002) 117 FCR 301 at 308.

Although, as Gleeson CJ observed in Berbatis Holdings there is a risk that categories, adopted as a convenient method of exposition of an underlying principle, might be misunderstood, and come to supplant the principle, the categories referred to in Samton Holdings serve to illustrate the extent to which the special disability relied upon by ZhXX in the present case falls outside those considered in earlier case-law. [17]; [18]

[17] Ibid at 63.

[18] (2002) 117 FCR 301

That is not to say that relevant special disability for the purposes of the equitable doctrine should be “boxed” into defined categories. As French J (as he then was) explained in ACCC v C G Berbatis Holdings Pty Ltd:

Australian case law has been concerned about unconscionable conduct within the framework of specific doctrines identifying particular classes of conduct albeit their boundaries tend to be blurred by the generality of the notion of unconscionability in equitable doctrine. One such class of conduct is the unconscientious exploitation by one person of the serious disadvantage of another to secure the disposition of property or the assumption of contractual or other obligations by the weaker party. The kind of disadvantage which will attract equity's intervention in such cases may have many faces. Their variety is so great that they elude satisfactory classification - Blomley v Ryan [1954] HCA 79; (1956) 99 CLR 362 at 405 (Fullagar J). [19]

[19] [2000] FCA 2 at [15].

Deane J also referred to the approach of Fullagar J in Blomley v Ryan in the following passage in Commercial Bank of Australia Ltd v Amadio:

The adverse circumstances which may constitute a special disability for the purposes of the principles relating to relief against unconscionable dealing may take a wide variety of forms and are not susceptible to being comprehensively catalogues. In Blomley v Ryan (1956) 99 CLR, at p 405 , Fullagar J. listed some examples of such disability: "poverty or need of any kind, sickness, age, sex, infirmity of body or mind, drunkenness, illiteracy or lack of education, lack of assistance or explanation where assistance or explanation is necessary". As Fullagar J. remarked, the common characteristic of such adverse circumstances "seems to be that they have the effect of placing one party at a serious disadvantage vis-a-vis the other. [20]

[20] Commercial Bank of Australia Ltd v Amadio [1982-1983] 151 CLR 447 at 474-475.

Thus the kinds of special disability which may invoke the equitable principles giving rise to relief against unconscionable dealing may take a wide variety of forms. They may, for example, include a “cultural disability” where a person is placed in a weakened position with regard to the other in a transaction by reason of being subject to cultural constraints enforced by social sanction if the transaction is not proceeded with. Such a person may well be placed in the position of being denied the capacity to make a worthwhile personal decision about the matter, such that, if the circumstances are known to the stronger party and unconscientious advantage is taken of the position, equity may well step in to provide relief.

Nevertheless, as also observed by French J in Berbatis, in quoting from Dietrich, Restitution: A New Perspective:

… the question of whether someone has acted unconscionably does not roam at large. Randomly asking whether people have behaved ‘unconscionably’ would be quite a meaningless exercise. Instead, such a question is asked only after certain specific requirements have been met. [21]

[21] Dietrich, Restitution: A New Perspective (Federation Press, 1998) at 48, quoted with approval by French J in Berbatis ibid at [14].

The present case differs from the usual in this area in the following respects:

(a) the complainant, ZhXX, as has been found, suffered from no special disability in the constitutional sense, that is, deriving from his lack of understanding of the English language or other circumstances peculiar to himself; and

(b) he did not suffer from any special disadvantage which could be described as “situational”: that is, deriving from particular features of a relationship between actors in the transaction. The fact is that ZhXX and KoXXal had no prior relationship of any kind, had no knowledge of each other and did not deal with each other in the transaction. The sale of ZhXX’s Property was undertaken by the Sheriff purportedly in the exercise of his statutory duty. This was not a transaction to which ZhXX was a party.

What is sought to be advanced on behalf of ZhXX is that he suffered a special disadvantage arising from the fact that his Property was the subject of a compulsory sale by the Sheriff.

However, I do not regard this as a special disability in the relevant sense. ZhXX’s will was not overborne to the extent that it was not independent or voluntary by anything other than the operation of the law. He was not in any position to make a judgment as to what was in his best interests, simply because, by reason of the enforced sale of his Property under the Sheriff Act, he was deprived by force of law of the opportunity to do so. He was not placed at a serious disadvantage vis-à-vis the other party by anything other than operation of the law.

The law applies equally to all who fall within its jurisdiction without exception. There was nothing “special” about ZhXX’s alleged disability for the purposes of the equitable doctrine.

Further, I do not regard KoXXal’s conduct in seeking to enforce the sale of ZhXX’s Property to him as unconscionable.

This is borne out by KoXXal’s evidence, which I accept.

KoXXal said that he purchased the Property at the second public auction conducted by the Sheriff. He swore that he bought the Property “in good faith; and without notice of any defect or want of title”.

By this I take it to mean that KoXXal had a legitimate expectation that the sale was conducted by the Sheriff according to law. In my opinion, he was reasonably entitled to take this approach.

Even though the price paid by KoXXal for the Property, when viewed objectively, may have been unreasonably low, by reason of the nature of the sale, being one conducted pursuant to the Sheriff Act, it was not in my opinion, unconscientious for KoXXal to seek to press the rights which, on its face, he had acquired under it.

Legal Principles – Sale of Assets Conducted by the Sheriff – a Short History to the Modern Form

The writ of fieri facias, or fi fa as it had become known, was one of the old common law writs which had the object of facilitating execution on a judgment. A judgment creditor could seek to satisfy his or her judgment by the issue of writs in the alternative to fi fa, including capias, sequestration and attachment. Other writs were also available which could be issued in aid of the principal writs of execution, such as venditioni exponas and distringas nuper vice comitem. For convenience, and in accordance with a long legal tradition, I will refer to the writ of fieri facias as the writ of fi fa.

The old common law writs of execution were formerly incorporated into the Rules of Court by Order 42. Rule 42.03 provided:

Judgment may be enforced as heretofore. – A judgment for the recovery by or payment to any person of money may be enforced by any of the modes by which a judgment or decree for the payment of money might have been enforced in the Court at the time of the passing of The Judicature Act 1883.

Rule 42.08 then provided:

Meaning of “writ of execution,” and “issuing execution”. In these Rules the term “writ of execution” shall include writs of fieri facias, capias, sequestration, and attachment, and all subsequent writs that may issue for giving effect thereto. And the term “issuing execution again any party” shall mean the issuing of any such process against his person or property as under the proceeding Rule of this Order shall be applicable to the case.

One of the writs which could be issued in aid of the writ of fi fa was the writ of venditioni exponas, which in the Latin meant literally “you expose for sale”.[22] Because this writ was supplementary to the writ of fi fa there needed to be in existence a current writ of that type to support the writ of venditioni exponas.[23]

[22] Black’s Law Dictionary, 6th edition, at 1555. Venditioni exponas was frequently abbreviated to “vend.ex.”

[23] T.L. & P.A. Finnegan (Timber) Pty Ltd v Beechey & Ors [1983] 2 VR 215 per Young CJ at 217.

The standard form of the writ venditioni exponas commanded the Sheriff as follows:

... that you expose to sale and sell or cause to be sold, the real and personal estate of the said [DEBTOR] by you in form aforesaid taken, and every part thereof, for the best price that can be gotten for the same, and have the money arising from the such sale before us in our said Court immediately after the execution hereof to be paid to the said [JUDGMENT CREDITOR] and have there then this writ. [24]

[24] Supra per Young CJ at 215-216.

This was commonly viewed as permitting the Sheriff, amongst other things, to sell the relevant property without a reserve price in place.

There is early authority which suggests that, even where a writ of venditioni exponas was issued the Sheriff was not entirely relieved of his duty in relation to price. In Slye’s Case (1619) Dodderidge J is reported as observing: “… where the sheriffe by vertue of the writ venditioni exponas sels the thing under the value, there he shall be discharged”. [25] [17th century spelling replicated]

[25] Godb 276; 78 ER 161.

However, later learning points to the writ as constituting a direction to the Sheriff to get the best price he can get on the day of sale, regardless of the market value of the property. In effect, the Sheriff is protected from redress on the part of the judgment debtor by the direction given to him contained in the writ of venditioni exponas.[26]

[26] Keightley v Birch (1814) 3 Camp 521, at p 524 (170 ER 1467 at 1469); Smith v Colles (1871) 2 VLR 195 at 197; Owen v Daly (1955) VLR 442 at 448; and Anderson v Liddell (1968) 117 CLR 36 at 49.

Nevertheless, in the absence of a writ of venditioni exponas, the Sheriff could be held liable in respect of sales conducted at an undervalue.

A case determined in England in 1814 during the Napoleonic Wars makes the point.[27]In Keightley v Birch & Anor Lord Ellenborough observed:

If a chattel worth £1,000 is put up to sale, and only £5 is bid for it, the sheriff ought not to part with it for that sum; and he may fairly say that it remains in his hands for want of a buyer. He ought to wait for a venditioni exponas, the meaning of which is “sell for the best price you can obtain.” [28]

[27] The case was determined the year before the battle of Waterloo in 1815.

[28] (1814) 170 ER 1467 at 1469.

In a Victorian gold rush case decided in 1871, Smith v Colles, Barry ACJ took a similar approach in relation to property consisting of mining plant sold by the Sheriff for £10 when its market value was £240. [29] His Honour said:

This property was sold by the Sheriff for £10, and within three weeks it was resold by the purchaser for £240. There must be some reason to account for this great disparity in price. … there is not a sufficient reason for the great disparity in the prices obtained at the two sales. [30]

[29] This was 2 years after the discovery in 1869 of the “Welcome Stranger” nugget discovered by John Deason and Richard Oates in Moliagul, Victoria, the world's largest nugget found to date.

[30] (1871) 2 VLR 195 at 196.

In Smith v Colles the Sheriff was held liable for negligence in circumstances where he sold the property on the misunderstanding that it was subject to a mortgage, when this was not in fact the case. The Sheriff of Castlemaine was held liable to the judgment creditor for the difference between the amount realised by the compulsory sale and the amount of the fi fa.[31]

[31] Ibid.

In Owen v Daly Dean J held that at common law the duty of the Sheriff in selling property is to act reasonably in the interests of both the judgment creditor and the judgment debtor in order to obtain a fair price. [32] This imposes a duty of care on the Sheriff. A sale made by the Sheriff pursuant to a writ of fi fa may be set aside if the Court is satisfied that it has not been properly conducted or that it has not been a real sale. His Honour said:

It is, I think, clearly established that at common law a sheriff selling the chattels, including chattels real, of a judgment debtor is bound to act reasonably in the interests of the judgment creditor and of the judgement debtor in order to obtain a fair price, not necessarily the market value, for it is well recognised that compulsory sales under legal process rarely bring the full value of the property sold [case references omitted]. The duty of the sheriff to act reasonably with due regard to the interests of both sides and his liability in damages if he fails to exercise reasonable care has been frequently stated. [Case references omitted.] I cannot think that a sheriff is in any different position so far as his duty is concerned from a mortgagee selling pursuant to a clause in the mortgage, subject to the fact that he can give safer title than the sheriff to the purchaser. [33]

[32] (1955) VLR 442.

[33] Supra at 446.

Dean J concluded:

Notwithstanding the very different risks involved in purchasing real and personal property, I do not think I can hold that the sale was at a fair price. The proper return was that the debtor’s property remained in his hands for want of buyers. The creditor might then have obtained a writ of venditioni exponas – see Chitty’s Archbold (14th ed), pp 830-1. Such a writ would authorise a sale for whatever the property may bring. I think plaintiff is entitled to some relief. [34]

[34] Ibid at 448.

Dean J in Owen v Daly, having been satisfied that the sale made by the sheriff was not properly conducted and was “not a real sale”, set the “so-called” sale aside, noting that this would avoid any award of damages against the sheriff, although the plaintiff’s costs were awarded against both the judgment creditor and the sheriff in all the circumstances.[35]

[35] Ibid at 449.

The duty of the Sheriff was also emphasised by the High Court in Anderson v Liddell.[36] Although the outcome was that the bid for the property in question was not regarded so low as to justify the sheriff refusing to accept it, and a finding was made that the sheriff had not breached his statutory duty and the sale was not set aside, the duty of a sheriff under the common law was spelt out.

[36] (1968) 117 CLR 36.

Consistently with the approach of Dean J in Owen v Daly, Barwick CJ observed in Anderson v Liddell:

No doubt the sheriff should know what he is selling to the point that he can decide whether or not a bid at the auction is illusory or unfair. .. It seems to me that the sheriff is entitled to accept at the auction any bid which is genuinely made and which bears a fair relationship to what is being sold. It is in this connexion that the sheriff must know what he is selling for it is rightly said, in my opinion, that he must obtain a reasonable price for what he sells. ... It is to be reasonable having regard to what is offered, namely, a debtors right title and interest, if any, and the circumstances of the sale. If there is no such bid, the sheriff is justified in returning, and he should return, a want of buyers. [37]

[37] Supra at 44-45

Kitto J in Anderson v Liddell followed a similar chain of reasoning. However, his Honour observed that, although a Sheriff who acts in breach of his duty may be held liable in damages, whether the sale could be set aside in the absence of collusion between the Sheriff and the purchaser was said to be “by no means clear”. Kitto J said in this respect:

If it was apparent to the sheriff that in fact or in all probability the bid was so far below the value that he would be acting unreasonably by accepting it, his proper course was to make a return that the property remained unsold for want of a buyer, and to refrain from selling at such a price unless commanded by a venditioni exponas to sell for what he could get: Keightley v Birch (1814) 3 Camp 521, at p 524 (170 ER 1467, at p 1469). For selling in that situation without waiting for a venditioni exponas he would be liable to an action for damages at the suit of the appellant, but whether the sale could be set aside in the absence of collusion between the sheriff and the purchaser is by no means clear. [38]

[38] Supra at 49

Reform in this area was recognised as being well over due in 1982. In General Credits Ltd v Beattie Young CJ observed:

The rules relating to the execution of judgments are principally to be found in Ords. 42 to 48 inclusive of Ch. I of the Rules of the Court. They originated in the English Judicature Act and in this State they have been the subject of very little revision since their first adoption. They are not only ill-adapted to modern conditions, but also fit uneasily alongside many of the practices which have been followed in the Court for very many years. The English Rules were revised in 1965 and I hope that the review of the whole of Ch. I of our Rules presently being conducted by the Rules Committee under the direction of the judges will result in considerable improvements. [39]

[39] [1982] VR 551 at 552

The Rules Committee undertook its work with care and thoroughness. Changes were introduced to the Rules of Court in 1986. A new enforcement process was created by Order 69. The new procedure introduced a warrant of seizure and sale. This replaced the former procedure replaced in Order 42 of the Rules of Court.

Amongst other things, the ancient common law writ of fieri facias was abolished as a process of execution on a judgment. Rule 69.02 provided, as it does to this day:

New enforcement process

The process of enforcement under this Order shall be used instead of the process of enforcement by writ of fieri facias.

By implication, the writ of venditioni exponas fell with it because this writ had no valid existence unless supported by a current writ of fi fa: T.L. & P.A. Finnegan (Timber) Pty Ltd v Beechey & Ors.[40]

[40] Ibid.

The Office of Sheriff

The office in Victoria can be traced back to between 1835 and 1851, when Deputy Sheriffs were situated in what was to become the colony of Victoria in the Port Phillip district. The appointment of Deputy Sheriffs for the district was made by the Crown and confirmed by the Governor of New South Wales.[41] The Victorian Sheriff's Office was created following separation of the Port Phillip District from the colony of New South Wales in 1851. The first Sheriff appointed in Victoria was Claude Farie, who was appointed by Queen Victoria in January 1852.[42] He served until 1870 and held his office under the Crown.[43]

[41] See: “Victoria Sheriff’s History”, http://www.bailiff.com.au/vic/vic-bailiff-history.htm, last observed 3 May 2012, the Bailiff/Sheriff website, http://www.bailiff.com.au/.

[42] See Public Record Office Victoria, Online Catalogue, “Sheriff’s Office, Supreme Court”.

[43] Supra.

As noted by Dean J in Owen v Daly the Sheriff in England was described as “the ministerial officer of the King’s Courts for the execution of all process, original mesne or final issuing from these Courts – in matters civil and criminal ”Encyclopaedia of the Laws of England, Sub. Tit. “Sheriff” (1st ed.), vol.11, p.533”. [44]

[44] Ibid at 449.

The office of Sheriff in Victoria came to be regarded as an officer of the Supreme Court.[45] By ss 196-225 of the Supreme Court Act 1928 which related to Sheriffs, they were regulated by the Act under provisions which formed Division 2 of Part IX of the Act, under the Part heading “Officers”. The Supreme Court Act 1986 to this day defines statutory functions of the Sheriff under Division 3 of Part 7 of the Act under the Part heading “Associate Judges and Officers of the Court”.

[45] Dean J in Owen v Daly ibid at 448-449.

On 1 January 2010 the Sheriff Act 2009 came into force and commenced operation. The Sheriff is now employed under the Sheriff Act pursuant to s 6 of the Act. This provides:

The sheriff

There is to be employed under Part 3 of the Public Administration Act 2004 a sheriff-

(a) for the purposes of court and enforcement legislation; and

(b) to assist in the administration of justice in Victoria.

The Sheriff and officers engaged under him or her are now administratively part of the Department of Justice and are directly employed by the Department.

Nevertheless, Chapter I of the Supreme Court Rules includes r 66.15 which provides a supervisory power which may be exercised by the Supreme Court in aid of the enforcement of a warrant of execution. [46] Rule 66.15 provides:

[46] Supreme Court (General Civil Procedure) Rules 2005 (Vic).

Order in aid of enforcement

(1) The Court may make such order as it thinks fit in aid of the enforcement of a warrant of execution and for that purpose may make an order that any person, whether or not a party-

(a) attend before the Court to be examined;

(b) do or abstain from doing any act.

(2) An application for an order under paragraph (1) may be made by the Sheriff

or other person to whom a warrant of execution is directed.

It was pursuant to r 66.15 that Mukhtar AsJ made his orders of 1 October 2010 dispensing with the need, subject to defined conditions, for a reserve price to be set on the sale. This was a perfectly valid order with which the Sheriff was required to comply.

Rule 66.15 in turn is governed directly by s 3(5) of the Supreme Court Act 1986 which provides that judgments of the Supreme Court may only be enforced in accordance with Chapter I of the Rules.[47] The 1986 Rules, as already noted, substituted a warrant of seizure and sale, amongst others, for the writ of fi fa as the mode of enforcement.

[47] Supreme Court Act 1986 (Vic), s 3(5) provides: A judgment in any proceeding must be enforced in accordance with Chapter I of the Rules of the Supreme Court and not otherwise. See Marriner v Smorgon [1989] VR 485, 508 (Ormiston J).

However, in my opinion, although the administrative arrangements as to the employment of the Sheriff changed following the introduction of the Sheriff Act in 2010, his status as an officer of the Supreme Court for the purpose of enforcing its warrants of seizure and sale and other such warrants issued out of the Court did not change. For these purposes the Sheriff remains an officer of the Court.

As such, the Sheriff is subject to the supervisory jurisdiction which may be exercised by the Court in aid of the enforcement of a warrant of execution pursuant to r 66.15. By these means, the supervisory powers of the Court continue to apply to the Sheriff in relation to sales conducted under the Sheriff Act in respect of warrants of seizure and sale issued pursuant to Order 69 of the Rules of Court.

However, the Sheriff also continues to be subject to the inherent jurisdiction of the Court in relation to sales conducted under the Sheriff Act in respect of warrants of seizure and sale issued pursuant to Order 69 of the Rules of Court, as he has always been in relation to the predecessor enforcement processes such as the writ of fi fa. I can find nothing in the Sheriff Act which in any way derogates from this important jurisdiction. Dean J in Owen v Daly found no difficulty in the Court setting aside a sale by its officer executing the process of the Court itself, where the sale was not properly conducted. [48] As stated by his Honour: “The Court has inherent jurisdiction to undo the acts of its officers”.[49]

[48] [1955] VLR 442 at 448.

[49] Supra.

In my opinion, it matters not that the Sheriff is now employed pursuant to s 6 of the Sheriff Act t by the Department of Justice. The Sheriff, as I have found in this case, purported to execute the process of the Court itself, and to this extent and for this purpose he was acting as the Court’s officer. He therefore remains subject to the Court’s inherent jurisdiction in carrying out the Court’s work.

Duties of the Sheriff under the Sheriff Act

Enter the Sheriff Act. A question arises as to whether the common law duties of Sheriffs developed by the courts administering writs of fi fa continue to apply to their contemporary statutory counterparts such as the warrant of seizure and sale, or has the common law duty of the Sheriff been abrogated or qualified by the statute? A second question arises at to what immunities from suit are conferred upon the Sheriff under the Act? A third question arises at to what duties are imposed on the Sheriff by the Act itself, according to its terms?

Relevant provisions of the Sheriff Act for the purposes of the present case are as follows:

Functions, powers and duties of the sheriff

7. Functions, powers and duties of the sheriff

(1) The sheriff has the functions and powers conferred, and duties imposed, on the sheriff by-

(a) court and enforcement legislation; or

(b) a warrant.

(2) In addition, the sheriff-

(a) has all the functions, powers and duties at law that the sheriff employed under section 106(a) of the Supreme Court Act 1986 had immediately before the commencement of section 58(1) that are not inconsistent with a function, power or duty referred to in subsection (1); and

(b) may perform any other function or duty, or exercise any other power, that he or she is authorised to perform or exercise under any other law.

Execution and return of warrants and other processes

13. Execution and return of warrants and other processes

(1) The sheriff must execute and return every warrant or other process directed to the sheriff as soon as practicable after receiving the warrant or other process.

(2) When executing a warrant or other process, the sheriff may only perform or exercise enforcement functions and powers that are reasonably necessary to execute the warrant or other process.

Sheriff may sell or otherwise deal with seized property

24. Sheriff may sell or otherwise deal with seized property

Subject to this Act, the sheriff may-

(a) sell property seized in accordance with the relevant court and enforcement legislation, or a warrant that authorises the seizure of property, for the purpose of applying the proceeds of the sale to the payment of a payable amount; or

(b) deal with property seized in accordance with a warrant that authorises the seizure of property.

Buyer of property sold by sheriff acquires good title

25. Buyer of property sold by sheriff acquires good title

(1) A person who buys property sold by the sheriff under this Division acquires good title to the property if the person buys the property-

(a) in good faith; and

(b) without notice of any defect or want of title.

(2) The sheriff is not liable in respect of the sale of property under this Division unless it is proved that the sheriff had notice, or might, by making reasonable enquiry, have ascertained, that the property was not the property of the person named or described in the warrant under which that property was seized.

(3) Nothing in this section limits or affects any right or remedy that the previous owner of property sold under this Division has or may seek otherwise than-

(a) against the property sold; or

(b) against the sheriff in the exercise of a power of sale under this Division.

Under s 24 (a) of the Sheriff Act the Sheriff is empowered to sell property seized in accordance with the relevant court and enforcement legislation. The phrase “court and enforcement legislation” is defined by s 3 of the Sheriff Act to include the Supreme Court Act 1986, regulations made under the Supreme Court Act and the Rules of Court.

In my opinion, the common law duties of the Sheriff which applied under the common law, by analogy, continue to apply to the Sheriff after the coming into operation of the Sheriff Act. The accepted principles governing the duties of Sheriffs which have developed under the common law are important protections for both judgment creditors and judgment debtors alike. They should not be swept away except by clear words which abrogate the duties or which seek to protect the Sheriff from suit, provided he observes the statutory requirements.

Section 25 is relevant. Pursuant to sub-section (2) the Sheriff is rendered not liable in respect of the sale of property under the Division (Division 5 of the Sheriff Act) unless it is proved that the he had notice, or might, by making reasonable enquiry, have ascertained, that the property was not the property of the person named or described in the warrant under which that property was seized. The specified exception does not apply in the present case. Further, pursuant to sub-section (3) nothing in s 25 limits or affects any right or remedy that the previous owner of property sold under the Division has or may seek otherwise than (a) against the property sold; or (b) against the Sheriff in the exercise of a power of sale under the Division.

However, the immunity from suit granted to the Sheriff under s 25(2) in my opinion applies only to sales of property sold validly under Division 5 where all of the statutory requirements have been met. Likewise, the immunity from suit provided by s 25(3) in my opinion applies only to sales of property sold validly under the Division where all of the statutory requirements have been met.

A sale conducted in circumstances where the statutory requirements have not been met, will not be a “sale of property under the Division”, under either ss 25 (2) or (3), and the immunities will therefore not apply.

Further, an order setting aside a purported sale conducted by the Sheriff resulting from the application of the common law or from a finding that the statutory requirements for a compulsory sale have not been met, will not, in the usual case, give rise to any liability being imposed on the Sheriff in respect of the sale of property. The Sheriff may be a party to such proceeding to ensure that he is bound by the result, however, no relief against him is likely where the sale is set aside. In this circumstances the immunities provided by s 25 are not likely to be relevant to the Sheriff.

The power of the Sheriff to sell or otherwise deal with seized property is strictly limited by s 24. This section defines the boundaries to be observed by the Sheriff in conducting sales and dealing with property. In terms of a sale, the Sheriff may only sell property seized:

(a) if the transaction can in truth be regarded as a “sale” and not an illusory sale founded upon a price which is so low that it could be said that there was no sale at all, or that it was not a real sale or that it was in fact illusory;

(b) if the sale is undertaken in accordance with the relevant court and enforcement legislation, or a warrant that authorises the seizure of property; and

(c) if the sale in undertaken for the purpose of applying the proceeds of the sale to the payment of a payable amount.

In my opinion, the Sheriff is also bound to apply the principles of the common law in the conduct of a valid sale under s 24.

The principles of common law to be applied to a Sheriff’s sale are these:

(a) The Sheriff is bound to act reasonably in the interests of both the judgment creditor and the judgement debtor in order to obtain a fair price;[50]

(b) A fair price is not necessarily the market value, for it is well recognised that compulsory sales under legal process rarely bring the full value of the property sold.[51] In making a determination as to the adequacy of the highest bid, the Sheriff is entitled to take into account that the sale, being a compulsory process, is usually one at which a full and fair market value for the property will not be expected and some allowance must be made for low prices being obtained at such sales;[52]

(c) In determining the fair price in all the circumstances, matters from the prospective buyer’s perspective must be weighed. Such factors may include: the fact that buyers must be prepared to complete their purchases on the spot; the fact that buyers, particularly in the case of real estate, will not have usually have had the opportunity to inspect the property sold (at least internally); the fact that the title to the property may be encumbered or it may be physically occupied, giving rise to risks for the purchaser in acquiring clear title or rights of occupation without undue expense or delay; and other such risks which may be attendant for the purchaser on the purchase;

(d) Another factor to be weighed in the balance will be the amount, if any, obtained for the judgment creditor after the expenses of the sale have been deducted;

(e) If it is apparent to the Sheriff that in fact or in all probability the highest bid received is so far below the true value of the property offered for sale that he would be acting unreasonably if he was to accept it, the Sheriff should not accept the bid and pass in the property;[53]

(f) if the Sheriff breaches his common law duty and sells property at a price which, in all the circumstances is unfair, the following consequences may follow:

(i) the transaction may be set aside.[54] On setting the transaction aside, no damages would arise in the usual case for which the Sheriff could be liable;[55] or

(ii) where the price obtained on the highest bid is so low that it could be said that there was no sale at all, or that it was not a real sale or that it was in fact illusory,[56] there would be no sale within s 24 of the Sheriff Act, and therefore no sale within Division 5 with the result that the immunity of the Sheriff from a suit in damages conferred by s 25 would be removed. There would not in truth be a “sale of property under this Division” for the purposes of s 25(2). In these circumstances, if the transaction is not set aside and loss and damage is in fact sustained, the Sheriff could be exposed to an award of damages at common law.

[50] Owen v Daly, ibid, per Dean J at 446.

[51] Owen v Daly, ibid, per Dean J at 446.

[52] Smith v Colles ibid, per Barry ACJ at 196.

[53] Owen v Daly, ibid, per Dean J at 446; Anderson v Liddell, ibid, per Barwick CJ at 44-45, and per Kitto J at 49.

[54] Owen v Daly, ibid, per Dean J at 446; Anderson v Liddell, ibid, per Barwick CJ at 44-45.

[55] Owen v Daly, ibid, per Dean J at 446.

[56] Owen v Daly, ibid, per Dean J at 447.

A finding that where the price obtained on the highest bid is so low that there was no sale at all, or that it was not a real sale or that it was in fact illusory, was relied upon by Dean J in Owen v Daly, where his Honour found on the facts before him:

Finally, I do not think this was a real sale at all. The bid made by the judgment creditor was based simply and openly upon the expenses of the sheriff and made after inquiry from him as to those expenses, for which he was liable to pay anyway. The only benefit from the sale was the princely sum of 4s and 11d. … Here there can hardly be said to have been a sale. [57]

[57] Owen v Daly, ibid, per Dean J at 447-448.

Whether the Second Auction Conducted in Accordance with the Common Law and the Sheriff Act

The second auction was not conducted in accordance with the common law or the Sheriff Act.

As to the breach of the common law duty, at the time of the second auction the value of the equity in the Property was approximately $165,000. This was known to the Sheriff’s officer conducting the sale who announced the amounts owing on the Property to the bidders prior to commencing the auction. The Sheriff’s officer also had in his possession the kerb-side valuation of the Valuer-General placing the market value of the Property at $630,000. There was some $465,000 owing on the Property. Nevertheless, it was knocked down to the highest bidder on the day, Mr KoXXal, for $1,000. This price bears no relationship to the evident market value of the Property or the ZhXX’s equity in the sum of approximately $165,000 which was put up for sale. In my opinion, and after taking into account all of the relevant factors to which I have referred, this price was so unfair that the Sheriff did not act reasonably in accepting it. The transaction cannot remain in place at common law.

Breaches of the Sheriff Act also occurred, which call for the purported sale to be set aside on additional grounds.

The Sheriff may only sell property seized in accordance with the relevant court and enforcement legislation. In the present case the Order of Mukhtar AsJ made 1 October 2010 was validly made pursuant to r 66.15 of the Rules of Court. It was made on the application of the Sheriff. The Order was quite explicit. The operative paragraph 1 of the Order provided that there be leave granted to the Sheriff to conduct a sale of the Property (in exercise of powers under a warrant of seizure and sale filed 9 November 2009) without a reserve price provided that such leave does not thereby derogate from, or relieve the Sheriff of a duty at law to the owner of the land when exercising a power of sale.

The duty at law to the owner of the land referred to in the Order could only have been intended to, and did in fact in my opinion, incorporate the common law duties to which I have referred, founded upon existing case law of long standing. For this reason alone, those common law duties applied to the Sheriff in the sale of the Property in this case.

The breach of the common law duties which I have found, also therefore resulted in a breach of the Order of Mukhtar AsJ made 1 October 2010, insofar as that order incorporated and indeed directed that the common law was to apply to the sale.

For this reason, the Sheriff did not sell property seized in accordance with the relevant court and enforcement legislation, which included the Order of Mukhtar AsJ made as an aid to its enforcement. Section 24(a) of the Sheriff Act was therefore not complied with.

Second, pursuant to s 24(a) of the Sheriff Act, the Sheriff may only sell property for the purpose of applying the proceeds of the sale to the payment of a payable amount due to the judgment creditor. If a sale was conducted for an extraneous purpose, it would not be a sale conducted validly under the Division.

The evidence was that the sale price of $1,000 did not even cover the costs of sale incurred by the Sheriff. The total costs of the Sheriff in conducting the second auction amounted to $1,152.73. This comprised search fees, a valuation fee and advertising expenses. These costs were known to the Sheriff’s officer at the time of the second auction. The sale was undertaken, yet nothing was yielded in reduction of the judgment debt in favour of the judgment creditor. The only proper inference to be drawn from these facts is that the sale pursuant to the second auction was carried through, not for the purpose of applying the proceeds of the sale to the payment of a payable amount due to the judgment creditor, for there were no such funds available, but for the purpose of offsetting, to a substantial degree, the costs incurred by the Sheriff in conducting the sale.

A sale conducted for this purpose is not permitted. This was therefore not a sale conducted within Division 5 of the Sheriff Act.

Further, the sale price in this case was so low as to give rise to an illusory sale. It was no sale at all within the meaning of s 24 of the Sheriff Act or Division 5.

If the purported sale to KoXXal is set aside, no loss or damage will have been sustained by ZhXX which is recoverable from the Sheriff. It follows that the immunities provided by s 25 will have no work to do and have no application.

I have no doubt that the Sheriff’s officer conducted himself honestly and conscientiously in carrying out the second auction. He found himself in a very difficult position under the Sheriff Act, where the precise nature of the duties of the Sheriff had not been authoritatively defined following the abolition of the writ of fi fa.

Nevertheless, whatever may be the inclination of the Court to support a public officer in the unprecedented circumstances of this case, the sale conducted pursuant to the second auction as a matter of law cannot be allowed to stand.

As to the purported rights gained by KoXXal following the second auction, although pursuant to s 25(1) of the Sheriff Act a person who buys property sold by the Sheriff acquires good title to the property, the purchaser only acquires such right in respect of a sale concluded by the Sheriff “under this Division”, which means Division 5 of the Act.

Because the sale was not one which was properly concluded under Division 5 of the Sheriff Act for the reasons which have been explained, s 25(1) of the Sheriff Act cannot apply and KoXXal does not gain good title to the Property under it.

Orders

Having been satisfied that the purported sale concluded following the second auction was not conducted in accordance with the common law, the order of Mukhtar AsJ made 1 October 2010, nor in accordance with Division 5 of the Sheriff Act, in the exercise of the inherent jurisdiction of the Court, the purported sale of the Property to Mr KoXXal for $1,000, is set aside.

I will hear the parties on costs.

---

1300 91 66 77

1300 91 66 77

首页

首页