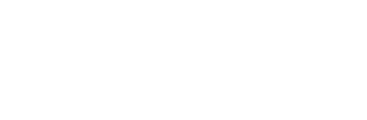

【Classic Cases】DXX v JXXX [2011] NSWSC 5XX

JUDGMENT

1 The issue in this case is whether the sum of $190,000 transferred by the plaintiff, Mr WX LoXX DXX, from his bank account to the bank account of the first defendant, Ms LiXXXn JXX, on 3 August 2010 was a very short term loan as he claims, or a gift as she contends. The underlying agreement or arrangement was oral.

2 The plaintiff borrowed the whole of the $190,000 in order to pay it to the defendant. The repayments are about $750 payable twice monthly. They substantially exceed his income of just over $600 per fortnight from workers compensation payments.

3 The second defendant is the first defendant's bank and was joined as a party only for the initial purpose of obtaining an order freezing the first defendant's bank account. It is convenient hereafter to refer to the first defendant as "the defendant".

4 The parties met in a brothel/massage parlour where the defendant was working as a prostitute. The plaintiff was one of her clients.

5 The parties agree that they had a regular sexual relationship. However, the extent of their relationship is otherwise contested. The question is whether their relationship ripened behind prostitution to the point where the plaintiff would gift the defendant $190,000, even though he could never afford to service it.

THE PARTIES

6 The parties immigrated to Australia from China, he in 1989 and she in 2008. He has some understanding of English although he required the assistance of an interpreter when giving evidence. She appears to be illiterate in English.

7 The defendant is aged 47 years. She was widowed in China in 1993. She has two adult daughters.

8 The plaintiff is aged 62 years and is unemployed. In 2004 he was divorced. He has one adult son who lives with him at his Burwood house. In 2005 he was injured at work and received a lump sum workers compensation payment of $155,000 which went towards his home mortgage debt. In 2006 he was again injured at work. Since then he has been unemployed and in receipt of periodic workers compensation payments, which in 2010 were just over $600 per fortnight. It appears to be his only income. His only assets appear to be his Burwood house and a flat in Shanghai.

9 He and his ex wife were the registered joint proprietors of the Burwood house and another house at Kingsgrove. In November 2004 the Burwood Local Court made consent orders in proceedings between him and his ex wife for the transfer of the Kingsgrove house to her and for the transfer of the Burwood house to him. She lives at the Kingsgrove house. Due to oversight, the necessary legalities for the transfer have not yet been attended to.

THE PARTIES' RELATIONSHIP UNTIL MID MAY 2010

10 The plaintiff received massage from time to time to relieve the pain from his work injuries. He says this was the reason he first visited the brothel (fronting as a massage parlour) where the defendant worked. However, he did pay her for sex as well as for massage on that and subsequent occasions.

11 According to the plaintiff, his relationship with the defendant was always one of paid sex and lasted from May 2010 until shortly after he transferred the $190,000 to her when he asked her to repay the money and she said she had lost it gambling at the casino.

12 According to the defendant, their relationship commenced in about November 2009 when he paid her for a massage and sex; became one of unpaid sex in about late June 2010 as a result of him expressing his love for her and promising and giving her expensive gifts; and terminated acrimoniously 10 days after the transfer of the $190,000, when he asked for the money back and she said she had lost it gambling at the casino.

13 In fact she lied when she said she had lost the money gambling at the casino.

14 According to the defendant, she worked in brothels (fronting as massage parlours) during the relevant period in the following suburbs of Sydney:

(a)At Hurstville in November/December 2009. She said that she had paid sex there with the plaintiff on two occasions, and that on the second occasion he asked her to be his wife and told her he owned two houses and a home unit.

(b)At Campsie from December 2009 until 15 May 2010. She says that the plaintiff tracked her down at the Campsie brothel in late January 2010, told her he missed her and paid her for sex; thereafter they had paid sex there at least fortnightly until 15 May 2010 when she went to China to visit her sick foster mother; and in about April to May he invited her to dinner a few times after they had sex but she always refused.

(c)At Enfield on Tuesdays and Fridays after 26 June 2010 when she returned from China. She says that he picked her up at the railway station on those mornings, bought her breakfast and then usually they would drive to his Burwood home where they would have sex. Then he would drive her to work.

15 According to the defendant, from May 2010 the plaintiff repeatedly expressed love for her and asked her to be his wife.

16 The plaintiff's evidence was that:

(a)In November 2009 he first saw the defendant when he visited the Hurstville brothel for remedial massage for the injury for which he received workers compensation. In oral evidence, his memory having been jogged by a document, he said it was on 12 January 2010.

(b)He next saw her in May 2010 at the Enfield brothel when he first paid her for sex, which she initiated, and a massage. Thereafter he regularly paid her for sex and a massage there.

(c)He never visited the Campsie brothel.

(d)After her return from China he picked her up at Strathfield station and drove her to work at the Enfield brothel because she asked him to as it was a long walk from the station to her work.

(e)He never took her to his Burwood home except on one occasion after he returned from China when she asked to see it, but they did not have sex there.

17 Telephone records in evidence show that the parties telephoned each other a number of times in late January, February, March and late April 2010. I do not think that the two calls in late April (for 134 seconds and 33 seconds respectively) 2010 are significant because they are near enough to his evidence of their relationship commencing in May. His other calls were diverted to voice mail and were measured in a few seconds - the longest was 19 seconds with three exceptions (putting aside the late April calls): his 36 second call on 26 January, his 57 second call on 11 February, and his 26 second call on 15 March. Her evidence was that he would call her or call her back after she called his number. Her evidence that he called her is inconsistent with the longer calls to which I have referred.

18 I accept the plaintiff's evidence that he initially telephoned the defendant's mobile phone because a masseuse had recommended he go to another masseuse and had given him a card with that phone number and the name "Lily" written on it. In fact the defendant used the name "Coco" not "Lily". His evidence was that the calls to his mobile phone from late January to April 2010, indicated on the telephone records, were from a woman whose identity he did not know. He said that he returned the calls but they were not answered. There is a question as to whether this is consistent with his longer calls to which I have referred, particularly the 57 second call.

19 On balance, I think that the longer calls provide some corroboration for the defendant's evidence. I conclude that he paid her for sex at times in the period from late January to late April 2010, although not necessarily with the regularity which she alleges.

THE DEFENDANT VISITS CHINA MAY/JUNE 2010

20 From 15 May to 26 June 2010 the defendant was in Shanghai visiting her sick foster mother. She stayed in the plaintiff's apartment. That came about because the World Expo was on in Shanghai at the time and she could not get accommodation there. The plaintiff's evidence was that he allowed the defendant to use his Shanghai apartment because he had a "good impression" of her. While she was in Shanghai, the plaintiff through his cousin paid the defendant RMB 5,000. The plaintiff's evidence was that it was a loan, which she requested, and that she repaid it to his cousin. A document in evidence from the cousin corroborates the plaintiff. The defendant's written evidence was that the cousin told her it was a gift from the plaintiff. In cross-examination the defendant's evidence was that the RMB 5,000 was an unwanted gift from the plaintiff via his cousin which she returned to the cousin. The weight of the evidence favours the conclusion that it was a loan which she repaid.

21 According to the defendant, while she was in China the plaintiff regularly telephoned her to declare his love and ask her to marry him. In these calls he told her (a) not to work any longer and he would pay her $1,000 per week; (b) if she did not want to stay at home he would buy her a caf and a car; (c) he would pay 20 per cent of the purchase price of a $490,000 home unit at Strathfield for her if she liked it; (d) he would give her $1,000 per week or more to repay the mortgage for the unit; and (e) he offered to transfer $20,000 to her account towards her mortgage in China, but she said no they would discuss it when she returned to Sydney. The plaintiff denied those conversations, although he conceded that there was some conversation during this period involving a unit at Strathfield advertised for $490,000. He said that she sometimes rang him from China thanking him for his help and indicating that she appreciated his assistance.

THE DEFENDANT RETURNS FROM CHINA

22 After the defendant's return from China, she and the plaintiff had sex on Tuesdays and Fridays. He claims he paid her, she says he didn't. They spoke regularly on the telephone. According to the plaintiff, after the defendant's return from China and as a result of their sexual relationship, the defendant repeatedly said that they should marry and that he should put her name on his property but he did not agree. She denied that evidence. According to the defendant, after her return from China they spoke regularly on the telephone; he again proposed marriage which she resisted; and he offered to buy her a massage shop which he would look after but she said that a caf was OK. The plaintiff agreed that they spoke on the telephone but otherwise disputed this evidence.

23 The defendant gave evidence that after her return from China and before the transfer of the $190,000, the plaintiff was generous to her in the following ways:

(a)On 28 June 2010 he gave her $500. He denied doing so.

(b)Whilst working Tuesdays and Fridays at the Enfield brothel, the plaintiff would usually pick her up from the railway station and buy her breakfast. They would then drive to his home at Burwood for sex. She would normally stay between 8.40 am and 9.50am. Then he would drive her to her work which was close to his house. The plaintiff admitted that he picked her up at the station; denied that he bought her breakfast; denied that he ever took her to his Burwood home for sex; and said that he only took her to his Burwood home once because she asked to see it. I accept corroborative evidence from the plaintiff's son, who lived with the plaintiff in the Burwood home and who usually did not leave for work until about 9.30 am. The son gave evidence that he had never seen the defendant there; and that on one occasion he had heard the plaintiff talking to a woman for about five minutes, but that they were not having sex. Rather, they were engaged in continuous conversation for those five minutes. The son said that he was in his bedroom at the time, and that if the plaintiff and the defendant were having sex he would have been able to hear through the walls because "the sound insulation system of that building is really bad. The weight of the evidence suggests that they did not have sex at his Burwood home.

(c)On or about 9 July 2010 the plaintiff paid her $20,000 in cash towards repayment of her mortgage in China. She said in cross-examination that she kept the $20,000 at home. He denied paying her this money. However, he agreed that he lent her $8,000 in cash at her request, as her foster mother in China was going to have heart surgery. That money has not been repaid. If the plaintiff lent her the $8,000, it is odd that he has not included a claim to recover it in these proceedings. That tends to suggest that he gave her at least $8,000.

(d)On or about 11 July 2010 he bought her a coat worth about $695 and cosmetics worth $570. He agreed that he accompanied her on the shopping expedition but said that she made the payments.

(e)On or about 25 July 2010 he gifted her $2,000 in cash to buy a computer. He said that both their computers were broken and he agreed to pay her $2,000 to buy a computer for him on the basis that she could use it for a few months. She still has it.

24 The defendant gave evidence that on or about 2 July the plaintiff picked her up at the railway station and drove to his Burwood home where they had sex. She said that on this occasion he told her that although he had divorced in 2004, his ex wife still lived with him in the house because she needed someone to look after her and relied on him. When she queried this, he replied that his ex wife was old and depended on him and he wanted to look after her. It is difficult to see why he would have said such a thing. The evidence favours the conclusion that his ex wife was living elsewhere and he was living in the house with his son: see [58(k)] below.

25 According to the defendant, on about 24 July she asked him when his ex-wife would move out and he said he was embarrassed to ask her. At the same time she expressed interest in buying a unit in Burwood. Later she indicated to him that she had inspected it and was not interested in it.

26 Did the parties have an emotional relationship? The defendant did not tell the plaintiff much about herself and her background. She did not give him her address or invite him to her home. She told him she lived at Chatswood with her sister: in fact she lived with her daughter elsewhere. Neither met any member of the other's family (other than on her visit to China when the plaintiff asked his cousin to lend her money).

27 As for the plaintiff's emotional state, he gave the following evidence as to events after the defendant's return from China:

(a)In late June 2010, in happy casual talk after sex he sometimes jokingly said to her, "Be my wife". He explained in oral evidence, "I had made a good impression on her and we had a common language".

(b)When he paid the defendant the $190,000 he "trusted her with my heart". He said that in Chinese culture people who respect their elders have a good heart and she had behaved well towards her foster mother in China in assisting her with medical expenses. He repeatedly said that at this time he had a "good impression" of the defendant.

28 I do not accept the plaintiff's written evidence that he never said that he wanted her to be his wife and that she only provided sexual services. I am satisfied that he indicated he would like to marry her and that he developed emotional feelings towards her. In their telephone discussions while she was in China, I think he probably expressed affection and attracted her with talk of financial support. However, I am not satisfied that it was couched in terms of such firm or large assurances or promises as she claimed in evidence: see [21] above. They would have been way beyond his financial capacity. I think that she developed no more than a slight emotional attachment towards him after her return from China, solely as a result of her perception that he was willing to provide her with some financial security. She understood that he had two houses and a home unit in Australia.

THE $190,000 TRANSFER

29 On or about 24 July 2010 the defendant told the plaintiff that she was interested in buying a home unit at Burwood with an asking price of $530,000.

30 On or about 28 July 2010 they visited a loan broker, as arranged by the plaintiff, for the purpose of obtaining a loan approval for the defendant to purchase a home unit. The broker advised as to the information that would be required to support the loan application, including a bank statement with at least 20 per cent of the loan amount in it.

31 According to the plaintiff's first affidavit sworn on 12 August 2010 in support of the urgent ex parte freezing order, in late July 2010 the defendant told him her husband was deceased and she wanted to marry him and said words to the effect:

I have no property in Australia. Could you do me a favour and temporarily transfer your savings into my bank account so that I can show the bank in support of my home loan application. Once it is approved I will return the money to you.

The plaintiff says that at first he disagreed but the defendant was persistent and asked again. He said words to the effect:

As soon as your loan is approved you must return the borrowed money to me.

She replied in words to the effect:

Yes I will return your savings money to you when my loan application is approved.

32 In the plaintiff's later affidavit made on 9 November 2010, he gave a virtually identical account of the conversation except that at the beginning of his words quoted above he added the words "I will loan you the money but". In the cross-examination of the plaintiff and in the defendant's submissions, something was sought to be made of the addition of those words as indicating that the plaintiff was seeking to bolster his case that the transfer was a loan.

33 The defendant's version was as follows:

(a)The plaintiff expressed love for her and said he wanted to marry her and on or about 28 July 2010 he said:

There are some funds in my loan account. I want to transfer the funds to your account.

I think this is unlikely. There were no funds in his loan account, he owed a small amount on that account, and he had to draw down the whole $190,000 as a loan in order to transfer it to her account.

(b)The plaintiff told her that he would first have to transfer funds from his loan account to his bank account. He wished to do so by internet banking to avoid a bank fee. He did not know how to transfer money through the internet. He gave her his online security device because she knew someone who did. She arranged for her daughter to transfer the $190,000, using his online security device, from his loan account to his bank account.

(c)On or about 3 August 2010 they had an argument during which she said that if he had not made so many promises to buy her a property, a caf and a car while she was in China, she would not be with him now. He said that he would keep his promise, he could not live without her, and that he would transfer money to her straight away and that "It is a gift to you". The plaintiff in evidence denied this conversation and said he could not possibly afford to buy her a property, a caf and a car.

34 On 3 August 2010 the plaintiff transferred $190,000 from his bank account to her bank account.

35 The defendant signed loan documents at the loan broker's office. The plaintiff was in attendance. A printout of the bank statement showing the transfer was provided to the broker.

36 The defendant submits that as she did not attempt to conceal from the plaintiff her photo identity card which she gave to the broker for photocopying and which contained her address, then she w as being open with him about her address. I accept the plaintiff's evidence that he never knew what her address was.

AFTER THE MONEY WAS TRANSFERRED

37 According to the plaintiff:

(a)Shortly after the money was transferred to the defendant's bank account, he asked her for a receipt and asked her to go to a solicitor's office to make a loan agreement. She refused. She denies that that conversation occurred.

(b)Her response worried the plaintiff. Consequently, he went to his bank and requested that the transfer be stopped. The bank informed him that the transfer had already gone through. He called the defendant's finance broker who told him that the loan had been granted to the defendant. I note that this is broadly consistent with a letter dated 4 August 2010 from the bank to the defendant advising her that her loan application had been approved in principle.

(c)He thereupon called the defendant and said that now that her loan application had been approved she needed to return the money he had lent her. She said no, wait, she would return the money to him soon.

(d)A similar conversation occurred the next day, 5 August 2010. The defendant thereafter apparently turned off her phone so he went to the Enfield brothel to find her but could not locate her. I note, however, that telephone records show they had a lengthy conversation that night.

(e)On 6 August 2010 he rang the defendant again but she did not answer his calls. I note that, contrary to his evidence, telephone records evidence that they spoke by phone that morning, as well as in the evening. At about 3pm he went to her place of work and asked her again to return the money. She said that it was gone and that she had lost it gambling at the casino. This caused him such distress that he hit his head against the wall, causing his head to bleed. The defendant admits that she told the plaintiff that she had lost the money in the casino. She says that that was on or about 13 August, and that he responded he had been to the bank and checked her account and there was $100,000 in it.

(f)On 7 and 8 August 2010 he telephoned her but she did not answer his calls. He waited at Chatswood railway station because she had told him she lived in the Chatswood area; and he spent all night at the casino hoping to see her. The first part of this evidence is contradicted by telephone records evidencing that in fact they spoke on the telephone on 7 August for quite a long time, once in the morning and again in the afternoon. They also had a lengthy conversation on the evening of 8 August. However, I accept that he did wait for her at Chatswood station and spent the night at the casino hoping to see her.

(g)On 9 August 2010 he asked her bank and the police to freeze her account, but was told they could not help him. At the police station he because extremely upset and was taken by ambulance to hospital where he remained with severe depression and anxiety for two days, 9 and 10 August. I note that the hospital case notes record that at the Burwood police station he had become distressed and asked the police to shoot him, and that he experienced chest pain. He was discharged from hospital shortly after noon on 10 August. He telephoned her from the hospital and asked her to visit him. She did not visit him. After he got out of hospital he visited her at her place of work and said words to the effect that he was admitted to hospital and that she didn't even visit him.

(h)On 11 August 2010 he saw a solicitor and instructed him to take legal action.

(i)He came under the care of a doctor whose records note that he had suffered extreme depression because he had been cheated out of a large sum of money by a female friend and had suffered major stress.

38 On 13 August 2010 the plaintiff commenced these proceedings. That day this Court made an ex parte order freezing the defendant's bank account.

39 The plaintiff contends, but has no evidence, that on 13 August 2010 the defendant was served with the freezing order, summons and affidavit of the plaintiff. The process server was not called to give evidence. The defendant's evidence was that she knew nothing about the proceedings until 16 August 2010 when she attempted to withdraw cash from the account and was informed of the freezing order. In the absence of evidence from the process server, I am prepared to accept the defendant's evidence.

40 According to the plaintiff, after the freezing order was made and the defendant's bank served with the order, he telephoned the defendant and said that there was only $100,000 in her bank account; she said she took his money to the casino to gamble; he said it was for the loan application which was now approved; and she said she was sorry, after she received the loan approval she did not need the money for that anymore so she used his money to go to the casino, but lost it. He testified to this in his affidavit of 18 August 2010, which appears to have been in aid of a continuation of the freezing order. She denied that evidence.

41 Meanwhile, after the defendant knew that the plaintiff wanted his money back, she withdrew a total of $70,000 on the following dates from her bank account:

10 August 2010

$10,000

11 August 2010

$10,000

12 August 2010

$50,000

42 The defendant's evidence is that she used the first amount of $10,000 to purchase watches as her daughter's wedding gift, and that her daughter took the balance of $60,000 to China on 19 September 2010.

43 On 23 August 2010 the parties signed a settlement agreement whereby the defendant would transfer the money in her account to the plaintiff if the plaintiff dropped the case. She says he did not honour the agreement and she terminated it. He says she did not comply with the agreement and terminated it.

44 On 8 September 2010 this Court ordered that the sum of $120,000 in the defendant's bank account be paid into Court.

45 The defendant's version of her communications with the plaintiff in the period between the payment of the money to her bank account on 3 August and the commencement of proceedings on 13 August 2010 is very different from the plaintiff's version. Her account is to the following effect:

(a)On 5 August 2010 she called him about a property she was going to inspect in Chatswood and asked him to come along. He says that occurred in late July 2010. I think that his recollection of the date is more likely.

(b)On 6 August 2010 the plaintiff picked her up at the railway station at around 8am, and they drove to his Burwood home where they had sex. She then obtained from him an assurance that he would pay her $1,000 per week to service her mortgage as she was not able to repay the mortgage without it. The next day he gave her $600 on account of the first payment of $1,000. The plaintiff denied all this evidence. He said he could not even afford to pay the interest on his own mortgage resulting from the loan of $190,000.

(c)On 7 August they inspected the Chatswood property. They were still on friendly terms.

46 According to the defendant's first affidavit, the plaintiff first expressed concern about the $190,000 payment on or about 10 August 2010 in the following circumstances. He picked her up at the railway station in the morning and they had sex at his home "as usual". Later that day he called her and said that his wife had found out about the money he had given her and he asked the defendant to transfer the money back. She said he had told her he was divorced. She asked him whether his wife or her was more important to him and how could he ask for the money back because of his wife. He said that the wife was threatening to commit suicide and he would give the money back to the defendant when his wife calmed down. The plaintiff denied this evidence.

47 These events could not have happened on 10 August because the plaintiff was in hospital on 9 and 10 August 2010. When confronted with the evidence of his hospitalisation, the defendant made a further affidavit in which she said that it could not have occurred on 10 August and that it probably occurred on 8 August. 10 August was a Tuesday. As the defendant, according to her own evidence, only worked at the brothel and (she says) went to his home for sex on Tuesdays and Thursdays, it is improbable that she visited his home on Sunday 8 or Monday 9 August. When this was put to the defendant in cross-examination she did not provide a satisfactory explanation.

48 As noted at [37] above, the plaintiff gave evidence that on 6, 7 and 8 August 2010 he rang the defendant but she did not answer his calls. I do not accept that evidence. Telephone records evidence a number of telephone calls between them, some for substantial periods of time, on those dates, as well as on 9 and 10 August when he was in hospital. When asked about these telephone records, the plaintiff conceded that he did speak to her on the telephone as follows:

(a)On 7 August she told him that she had been in the casino. Later, he told her not to go to the casino and that he would wait for her at Chatswood (railway station). She had previously told him she lived in the Chatswood area.

(b)On 8 August 2010 he indicated he was very angry that she went to gamble at the casino.

(c)On 9 August 2010 while he was in hospital he told medical staff what had happened. They urged him to call her. He called her and asked her to come to the hospital.

49 According to the defendant:

(a)on the morning of 13 August the plaintiff picked her up at the station;

(b)they had sex at his Burwood home;

(c)he said he wanted her to transfer the money to him;

(d)that upset her;

(e)she said "I lost the money in the casino";

(f)he said his wife had been to the bank and checked the defendant's account and there was $100,000 in it.

50 I have earlier mentioned the defendant's evidence that on or about 19 September 2010 the defendant's daughter went to China with the sum of $60,000, being the bulk of the plaintiff's funds withdrawn by the defendant from her bank account between 10 and 12 August 2010: see [41] above. The freezing order of 13 August 2010 did not prevent this because it only froze the money in the defendant's bank account and did not extend to the money she had already withdrawn. This may well have been because the defendant, on her own evidence, had deceived the plaintiff by telling him that she had lost his money gambling. Therefore he would not have expected her to still have most of what she had withdrawn in her possession.

51 On 20 September 2010 the plaintiff received a letter from his lender stating that his repayments had increased to $747.82 per fortnight.

52 I accept the plaintiff's evidence that the defendant's refusal to pay back the $190,000 has caused severe financial hardship and left him in a position where it is impossible to pay his home loan, and that he has been relying on friends and family to assist him to make repayments. Financial records indicate that he reduced his loan account by payments totalling about $18,000 between September and November 2010. His evidence suggests that the source of those payments was family and friends.

53 In cross-examination the defendant admitted that she allowed the plaintiff to transfer $190,000 into her bank account but that she never had any intention of buying a property. She said that this money was for sex only. She agreed that the loan broker told her that her home loan was approved but she didn't really care because it wasn't about getting money for a home loan; it was about getting the plaintiff's money.

54 On 7 September 2010 the defendant applied for an apprehended violence order against the plaintiff. She told the police that she had been in a relationship with him for three months since May 2010. The application was heard in December 2010. Under cross-examination in those proceedings she gave the following evidence. He had transferred money into her bank account. She had made a home loan application which was approved in August 2010. Afterwards he asked for the return of the money. It was impossible for her to return it because she had "contributed". Because he had promised to give her that money she had had a sexual relationship with him. When cross-examined about those proceedings in the present proceedings, she said that she believed she was entitled to the money because she had free sex with him from 29 June to about 10 August 2010. That was her contribution.

55 On 2 December 2010 the plaintiff wrote a letter to his bank recounting the events of 3 August 2010 in a way that is consistent with the evidence he gave in these proceedings. He requested a copy of the note that the bank officer made on that occasion.

56 On 14 February 2011 the NSW Police Force wrote to the plaintiff concerning his fraud complaint against the defendant and advising that the complaint had been assessed as civil in nature. His fraud complaint to the police is not inconsistent with his allegations against the defendant in these proceedings.

57 The defendant submits that she needed the $190,000 to pay for the purchase of a property for $560,000, that the loan would not receive final approval unless the deposit was there, and that this supports her evidence that the transfer was a gift. The submission sits uncomfortably with several matters. First, the sum of $190,000 was much more than would have been needed for a deposit. One of the curiosities of this case is that there is no explanation of why an amount of $190,000, rather than some other amount, was chosen. Secondly, the plaintiff quickly withdrew a third of the money, and would have withdrawn more except that she was frustrated by the freezing order. Thirdly, the defendant said in oral evidence that she never had any intention of ever buying a property. Fourthly, the defendant had $38,000 in her bank account to which the $190,000 was transferred. According to her evidence, she also had at home another $20,000 which he had given her: see [24] above. Although I have not accepted that evidence, I have accepted that he gave or lent her at least another $8,000. It is unclear whether she had additional cash resources. I am not prepared to say that she did not have a 10 per cent deposit from her own resources - if indeed she ever intended to purchase a property, which she did not.

CREDIT

58 The defendant submits that the plaintiff's credit was damaged in the following respects, some of which I accept:

(a)In a later affidavit the plaintiff added the words "I will lend you the money but" to his earlier affidavit account of the oral loan agreement. The defendant criticises this as tailoring evidence to bolster the plaintiff's case. I think that the earlier account made it quite clear that it was a loan agreement. Both affidavits set out the effect of the word used. I take into account that this conversation is central to the case. Nevertheless, the earlier affidavit was prepared urgently for a freezing order application. Further refection on the effect of the words used which produce a few more words to the same effect is not necessarily sinister.

(b)The plaintiff's affidavit evidence of a relationship with the defendant which was simply one of payment for sexual services concealed the truth that he had developed romantic feelings towards the defendant. I agree.

(c)The defendant submits that the plaintiff's denial of any communication with the defendant in the period prior to May 2010 is contradicted by the telephone records and that this supports her evidence that they had a paid sex relationship prior to May 2010. As discussed earlier, I accept that this is so.

(d)Whilst under cross-examination the plaintiff communicated with another witness, his son, concerning the telephone records. He should not have done that while he was under cross-examination. On the other hand, the son merely carried out a comparative and helpful analysis of the telephone records, which was tendered and which I accept. The defendant does not dispute it. It puts the telephone records in a different light than what would have been the case if the analysis had not been carried out.

(e)The plaintiff's affidavit evidence of not speaking to the defendant in the period from 5 August was contradicted by the telephone records. I accept that is so.

(f)The defendant submits that the defendant made an admission, when it was put to him in cross-examination, that he would say whatever it takes to get his money back. The submission is dependent upon correcting the transcript of his answer "Of course I want to get my money back" by putting a full stop or comma after "Of course". I am not satisfied that any such correction is warranted nor that the plaintiff made any such admission.

(g)The defendant submits that the plaintiff lied when he said that on the occasion he first had sex with the defendant he went to the massage parlour for remedial massage. The defendant further submits that he went to such places to pay women for sex: the plaintiff denied this in evidence. Given the plaintiff's injury for which he required remedial massage, I am not prepared to conclude that he lied. He was, however, frank that he paid the defendant for sex as well as a massage.

(h)The defendant submits that the plaintiff's evidence about asking the plaintiff to return the money is unreliable because in cross-examination he said that he told her it was impossible to put her name on his property when he asked her to return the money. The defendant's criticism is that it is implausible that he would be simultaneously having a conversation in which he was demanding the money back and she was asking to have her name on the property, and that this is not mentioned in his affidavits. There is some force in the criticism. However, the explanation may lie in an error by the plaintiff as to when the conversation occurred.

(i)The plaintiff denied in an affidavit that he ever asked the defendant to marry him. However, in cross-examination he admitted that in happy casual talk after sex (after her return from China) he would say to her "Be my wife". I agree that this damages the plaintiff's credit.

(j)The plaintiff's affidavit evidence that their relationship was only for paid sexual services was not truthful. I agree. I am satisfied that he developed emotional feelings towards her.

(k)The defendant alleges that the plaintiff told her that his ex-wife lived with him at the Burwood house. The defendant invites the inference from the non-calling of the ex-wife that she was in fact living at the Burwood house. The plaintiff's explanation for not calling his ex wife was that he was embarrassed to do so. There would certainly be embarrassment in telling his ex wife that he had lent $190,000 to a prostitute. However, it seems implausible that the ex-wife would be living in the Burwood house when, if the defendant is to be believed, the plaintiff and the defendant has sex there two mornings per week. Further, the Burwood house is an old two bedroom house. The plaintiff occupied one bedroom and slept in a single bed. His son occupied the other bedroom. There was no bedroom available for the ex wife. Moreover, there had been a Local Court order giving the Kingsgrove residence to the ex-wife and the Burwood home to the plaintiff. The plaintiff and his son said in their affidavit that the ex-wife lives at the Kingsgrove house. The son added that sometimes his mother visits him at home. The defendant submits that as this evidence was couched in the present tense, they did not give evidence that the ex-wife did not live at the Burwood house at the relevant time. I do not accept the submission. Read in context, their evidence should be understood to have been referable to the relevant time. The contrary was not put to them in cross-examination. I consider that the weight of the evidence favours the conclusion that the ex-wife was not living in the Burwood house at the relevant time.

(l)The defendant criticises the plaintiff for not calling the bank officer and the policeman to corroborate his evidence noted at [37(g)] above. There is evidence, which I accept, that the bank officer to whom he spoke is no longer with the bank. The plaintiff said that the police made a written notation at the time but no such document was produced in response to a subpoena. However, I do not think that the absence of the record or the failure to call the police officer is particularly significant given that the plaintiff undoubtedly was taken from the police station to the hospital in an extremely distressed condition.

(m)The defendant submits that the plaintiff's track record of "gift giving" to the plaintiff cuts across his allegation of a loan. The parties' respective evidence on this point has been discussed at [23] above. I am prepared to accept that he gave her at least $8,000 and that, contrary to his denials, he gave her a computer and some gifts on a shopping expedition. However, the transfer of $190,000, being of vastly greater value, is of a very different nature.

59 The credit of the defendant was also damaged including in the following respects:

(a)The defendant deceived the plaintiff by leading him to believe that she intended to buy a property and was interested in a home loan and by allowing him to transfer $190,000 into her account at that time when, as she admitted, she had no intention of ever buying a property and it was about getting the plaintiff's money: see [53] above. A logical explanation for her deception is that it was a ruse to persuade the plaintiff to transfer the $190,000 to her account. That also helps to explain why she quickly withdrew so much of that money in cash, keeping the bulk of it in her house until she could shift it abroad.

(b)The defendant's affidavit evidence that the $190,000 was a gift sits uneasily, to say the least, with her oral evidence that she was "entitled" to it because of the free sex she claims she gave him for about six weeks prior to 10 August 2010. This sense of entitlement does not evidence the plaintiff's intention to give her the money, rather it seems to explain why the defendant was remorseless in keeping it despite the plaintiff's protestations. Her evidence confuses a sense of moral entitlement to the money with legal entitlement to that money. Her evidence that she was entitled to keep the money because of her sexual "contribution" suggests that the reason she kept it was not because the plaintiff had given it to her unconditionally but because she felt he owed it to her for sex. That conclusion is not significantly affected by her agreement in re-examination that she also factored in as her contribution an emotional element and a feeling of some security in her relationship with the plaintiff.

(c)She lied to the plaintiff when she said she had lost the $190,000 gambling.

(d)As discussed above at [46] - [47], I think her evidence was unreliable in relation to the occasion when she alleges he first asked for the $190,000 back, which she first attributed to Tuesday 10 August and then to 8 August.

(e)It is a relatively minor matter, but she claimed that their sexual relationship commenced in November/December 2009 yet the telephone records only evidence telephone communications between them commencing in late January 2010.

CONCLUSION

60 I have concluded that the plaintiff, contrary to his affidavit evidence, had a paid sexual relationship with the defendant earlier than May 2010, that he later developed an emotional interest in the defendant and that there was then discussion of marriage. I do not think she ever had more than a slight emotional feeling towards him, which was brought about entirely by interest in what he might provide for her materially. I think that he attracted her materially by letting her use his Shanghai flat when she was in China, lending her a small amount of money while she was there, giving her at least $8,000 for her mother's heart surgery, buying her items on a shopping expedition, giving her a computer and talking to her about financial support.

61 Notwithstanding the significant damage done to the plaintiff's credit in cross-examination, I have concluded that the plaintiff transferred the $190,000 to the defendant's bank account on the basis that it was a loan. The plaintiff did not intend to gratuitously give the defendant the money. I also generally accept his version of events after the transfer was made. My principal reasons follow.

62 First, the plaintiff did not have the financial capacity to service his borrowing of the $190,000. Although he was emotionally interested in the defendant, I do not accept that he was so irrational as to borrow $190,000 and gift it to her when the periodical repayments substantially exceeded his low income from workers compensation.

63 Secondly, a rational explanation is that he borrowed that sum with the intention of lending it to her for a very short time until her imminent home loan application was approved. On the defendant's evidence, he gave her the money simply because of his romantic interest in her. According to the defendant, he suddenly said, "There are some funds in my loan account. I want to transfer the funds into your account". I have difficulty accepting that he said this because there were no funds in his loan account. He had to draw down $190,000 in his loan account, thus incurring a very large liability where virtually none had previously existed. Before the transfer the defendant made a loan application through a finance broker and a healthy bank statement was needed to support the application. There is evidence, which I accept, that the broker advised her that a bank statement should be provided showing that there was 20 per cent of the funds sought to be borrowed. I think that this provides the explanation for the transfer of the $190,000 into her bank account. It is consistent with the plaintiff's evidence that it was a loan to be repaid when the application was approved. It provides a rational explanation for the transaction given his financial circumstances.

64 Thirdly, on the central matter of their oral agreement or arrangement I formed a favourable impression of the plaintiff when he gave oral evidence.

65 Fourthly, the plaintiff's collapse at the police station required him to be taken by ambulance to the hospital where he remained for two days, 9 and 10 August, suffering from depression, anxiety and panic caused by a great shock. His evidence of the defendant's prior conduct would explain why he suffered such a shock. According to the defendant's affidavit evidence, their relationship continued normally until 10 August. I have explained earlier why I cannot accept her attempt in oral evidence to move her account of the alleged events of 10 August to an earlier date: see [46] above.

66 Fifthly, the matters affecting the defendant's credit discussed at [59(a), (b), and (c)] above weigh particularly heavily with me.

ORDERS

67 The plaintiff has been successful.

68 The orders of the Court are as follows:

1.Judgment for the plaintiff against the first defendant in the sum of $190,000 plus interest from 3 August 2010 to the date of judgment at the prescribed rates pursuant to s 100 of the Civil Procedure Act 2005.

2.The first defendant is to pay the plaintiff's costs.

3.The exhibits may be returned.

1300 91 66 77

1300 91 66 77

HOME

HOME