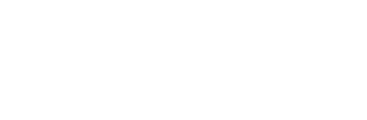

【Classic Cases】LaXXkh Pty Ltd v CXX & AXXr [2010] FMCA 7XX

ORDERS

(1) The Respondents pay the Applicant:

(b) Damages of $10,000 for damage to reputation;

“I did see a rib cage elsewhere, but I wanted to do something that was a bit more medical, and looked a little bit like an X-ray; had kind of a grainy effect to it. Like the – this sounds really silly, but almost like it was kind of a magical T-shirt, where you could X-ray your rib cage. So I wanted to apply an effect, or draw the rib cage in a way that would give that effect, and I do think that was my original idea, to have that kind of grainy look to it

(P–41).”

Ms NXXy sketched a ribcage from a photograph of human ribcages she saw on the internet. Over that, she applied dots using a ruler and felt pen to create the impression of the design. This was not easy (P–45).

Ms NXXy did not retain the original sketch of the dots out of laziness (P–46), and she had to scan it in to make it work (P–47).

In response to a question from me as to whether the trend for skeleton-type garments was still extant, she said “especially with prints, once they go into the marketplace and, I mean, my experience with customers is once they’ve seen something they generally don’t want to repeat it again, when it’s that specific. So they might want to work within the trend but no so specifically within something so tight as a print or, you know, a garment shape, or something like that” (P–48).

The question of degree of originality required to establish the subsistence of a copyright, in circumstances where one drawing may be based on another was considered in authoritative terms by the Full Court of the FeXXral Court in Interlego AG v Croner Trading Pty Ltd [1992] FCA 624; (1992) 39 FCR 348. Gummow J, with whom Black CJ and Lockhart J agreed, said at P-379:

“...generated and cultivated a reputation as being an innovative brand that prides itself on its garment designs which are of good quality and which appeal to a range of fashion conscious women in their 20s and 30s. Since launching, the applicant has built up a substantial reputation in the LaXXkh brand.”

In 2000 or thereabouts, the applicant bought a factory in China. This predated the employment of Ms KiXXton in 2002, but I accept that she is in a position to give that evidence, given the company’s records available to her.

The applicant still continues, however, notwithstanding the purchase of its factory in Shanghai, to use third party manufacturers on occasion (P–77).

The applicant employs designers, one of whom was Ms NXXy. Designs, once prepared, are sent to the factory in Shanghai, as is the relevant artwork (P–59). They are sent both electronically and in hard copy.

The applicant’s processes of advertising and promoting their material to wholesalers include the creation of look-books, which are made available to wholesalers who visit the applicant’s premises, as well as substantial advertising in magazines. Ms KiXXton has exhibited very substantial amounts of such advertising.

Following the creation of the Skeletor tank design by Ms NXXy, it was sent to China and the garments were made for the applicant. Copies of the garment were offered for sale in about late May 2009, and the vast majority of the sales that eventuated took place in May and June

(P–74).

There were no specific paid advertisements for the Skeletor, but all 1153 of the applicant’s Skeletor garments were sold (subject possibly to a small number being returned as deficient or the like).

Ms CXX, who was the only witness cross-examined on behalf of the respondents, has deposed in her affidavit (exhibit R2) affirmed on

12 August 2010 that she started her own business of importing shoes from China in about 2004. At the end of 2008, the Global Economic Crisis took a big hit on her business, and she had just given birth to her first child. As a result of the concomitant stresses, she decided she would branch out into other areas of wholesale and at about the same time, her husband, the second respondent, agreed to quit his job and they decided to start a clothing business together.

In December 2008, they registered the New South Wales business name BXhX Australia in their names. Before doing so, Ms CXX flew to Guangzhou “in the end of 2008” to search for factories from which she could buy garments. She eventually picked a factory named KeXX Clothing Industry Factory “as it is not a very big factory and is perfect for a small entrepreneur like myself.”

She dealt, at that factory, with SuyXX XiXX. At the beginning of 2009, Ms CXX also hired BilXXn XiXX, for the latter to be responsible for quality assurance and accounting. Ms CXX deposed that BilXXn XiXX checks quality of clothing and otherwise assists her in her business in China.

Ms CXX deposed that she imports about two to three hundred pieces of fashion garments into Australia every week which usually arrive on Thursdays and Fridays, and quite a few of her retailer customers come in on Mondays and Tuesdays to look at the new shipments. The target customers range from women in their 30s to 60s.

Despite a difficult start, business improved in 2009.

At some time “in the beginning of mid-2009” Ms CXX “realised that ribcage designs had become very popular.” She said, “I gained this knowledge because Sass & Bide has a metallic rib cage design that sold very well.”

What happened thereafter is a matter of controversy.

What is not the subject of controversy is that by late August, or at least September 2009, Ms CXX’s supplier in China had manufactured not less than about 150 of the Skeletor tank design garments. The garments appear to have been very similar to the applicant’s Skeletor tank-top designed by Ms NXXy, and the design itself is conceded to be, to all effects and purposes, identical.

It should be noted that when I say identical, this means that it is identical in the sense that each or almost every one of the various little dots placed by Ms NXXy to produce the design has been exactly reproduced in the BXhX garment ultimately sold.

On 20 September 2009, Ms KiXXton, who was shopping with her family, bought a BXhX Skeletor tank-top at the Funky Femme shop in Coogee (see exhibit JK-21).

It was for sale at a substantially lesser retail price than the applicant’s retailers would have sold it for.

The applicant, in fact, sold 282 Skeletor garments in Sydney, which

Ms KiXXton says was an average sale, and I accept that evidence.

I also accept Ms KiXXton’s evidence that the Funky Femme shops are in high profile locations and are well presented. I further accept her evidence that Funky Femme would not sell that garment, simply because it would cost too much for the sort of clientele that Funky Femme attracts. It should be noted that Ms KiXXton is, clearly from the evidence she gave and the way she gave it, very experienced in matters to do with the clothing industry.

In order to understand the controversy between the parties, which was essentially whether or not it was Ms CXX who caused the fake reproductions of the Skeletor tank-top to be made or some other party, it is important, at this point, to address the evidence of the parties. I have already addressed the evidence of Ms NXXy, whom I should make it clear was an excellent witness who was obviously telling the truth.

The evidence of Ms KiXXton

Ms KiXXton has been working in the fashion industry since 1999 and in Sydney since 2000. As earlier indicated, she started working for the applicant in 2002, and was promoted to her current role of general manager in 2009. I have already referred to the extensive production of garments and advertising deposed to by Ms KiXXton.

Ms NXXy created the Skeletor graphic work in February 2009 and on or about 2 April 2009, the applicant sent the orders to China for the production of the garment. Two samples of that garment featuring the graphic were sent from China to Australia for approval, and the order went ahead in due course.

On or about 8 May 2009, the applicant’s factory shipped 1153 units of the Skeletor garment to Australia, and they were part of the applicant’s April range.

1141 units of the garment were sold to wholesale customers but as I have said, it was Ms KiXXton’s oral evidence that all of the run was sold.

As indicated, on 20 September 2009 Ms KiXXton bought the BXhX Australia garment from the retail store Funky Femme. On 5 October 2009, she instructed MidXXXXons to send letters of demand to Funky Femme who, through their solicitors, identified BXhX Fashion as the party from whom they had bought the garment. Funky Femme immediately withdrew the remaining 20 garments it had in its possession from sale, and returned them to BXhX Fashion.

Also on or about 5 October 2009, Ms KiXXton instructed MeXXrs MidXXXXons to send letters of demand to the respondents, which were the subject of a response from solicitors RoXXXick B HaXXXs & Co to MidXXXXons claiming that approximately 150 garments were manufactured in China and were sold at $5 profit.

A letter was sent to MidXXXXons from the first respondent dated

11 November 2009 but sent on 12 November 2009. The terms of that letter speak for themselves. In summary, Ms CXX asserted that she did not mean to copy the applicant’s design and that “the rib cage was in fashion and we wanted to use this idea only. We did 148 pieces which arrived here in late August. We have sold out of this design ... and we take full responsibility for our actions.” (exhibit M to Ms CXX’s affidavit).

Ms KiXXton asserted that LaXXkh only sells its branded garments to select boutiques within Australia and New Zealand. She asserted that when these designs are copied by other businesses and targeted to a similar market to the applicant’s market, the claim of originality in the garments is lost. She asserted that such circumstances give rise to a diminution in the LaXXkh brand as a whole. She went on to say, at paragraph 34 of her affidavit (the above is all a paraphrase of the affidavit):

The Applicant’s continued success is heavily dependent on the Applicant maintaining exclusivity and originality of its designs as the Applicant credits its success to the talent and skill of its design team and the effort and resources that go into creating its products which have popular appeal with its target market of fashion conscious women. The applicant takes all possible steps to protect its designs and exclusivity of these designs. The Applicant has taken action against numerous fashion houses that have copied its original designs.”

She went on to give evidence as to the applicant’s reputation in the LaXXkh brand, and that the BXhX garment was sold in retail stores in close proximity to retail stores to which the applicant sells. She gave uncontradicted evidence that the LaXXkh garment was sold for a recommended retail price of $44.95, and that she purchased the BXhX garment for $33.

In oral evidence-in-chief, Ms KiXXton gave evidence that the applicant’s office is in Surry Hills which was said to be, and indeed clearly is, a kind of centre of the fashion industry in Sydney. She said that wholesalers and retailers come to look around, and look at the applicant’s look-books.

Tellingly, she said that the applicant would know if anybody else was using the Skeletor tank design in Australia. She said no other wholesaler was using this design in Australia (P–56). What she said was:

And have you found any other people using this particular design, in Australia?... No. No.”

I would interpolate at this point and repeat, if I have not already made it clear, that Ms KiXXton was an impressive witness. The nature of her answers and the way that she gave them inspired every confidence in her as a witness both of truth and expertise. When she did not know something, she was candid in her admissions, and her answers were generally given with an extremely authoritative mien of a person talking about a subject in respect of which she was in full command.

She was a witness of truth and I accept all of her evidence in that sense. There is, however, one minor aspect of it, to which I shall come, that I am unable to accept.

Based on Ms KiXXton’s evidence, I accept that no other wholesaler has used this particular design.

Ms KiXXton gave evidence under cross-examination as to what are called repeats. These are further orders for particular garments. These are conducted at the request of customers, and most involve one or two repeats. The average turnaround time for repeat orders is about four to five weeks (P–70). Ms KiXXton described Funky Femme as being towards the lower end of the fashion market with nothing expensive (P–75). She did, however, confirm that Funky Femme stores look good, but would not sell the applicant’s products as they would be too expensive (P–76).

Ms KiXXton expressed the view that it was very improbable that BXhX’s importation of garments was limited, as was asserted, to only about 150. She said that China was a mass market where it was difficult to get a small run and that, indeed, that is one of the reasons why the applicant has its own factory (P–77.)

She went on to say that her knowledge of production in China was based, as it were, not on being directly involved, but from her experience in the industry generally. She said, however, and I accept, that it is an industry concerned with big orders, and that often the applicant has to order 1000 metres of garment at a time. She said, and I accept, that it is hard to order under 300 units, and that it was difficult to get “those small runs” out of China (P–79).

I have no doubt that Ms KiXXton was telling the truth when she gave this evidence. What I think, however, is more probable is that Ms CXX may have been able to get smaller runs on occasion. LaXXkh is an upmarket brand dealing in substantial numbers of sales.

It may well be possible for smaller operators using inferior quality products to accommodate smaller runs.

That is not to say that Ms KiXXton’s evidence is incorrect. Rather, in this respect at least, while I accept Ms KiXXton’s evidence as far as it goes, I am not satisfied that it has been established that it is more probable than otherwise that more than 150 garments were imported by BXhX.

The evidence of Ms ToXXy

Ms ToXXy’s evidence was given orally. She attended only on subpoena. She was a former employee of BXhX who started in November 2009 as a sort of office administrator or manager. She was not the only employee. Her employment ceased in March 2010 (P–81).

She described how a letter was received from MidXXXXons and Ms CXX asking her to ring MidXXXXons on her behalf. At P–83 of evidence-in-chief, she said:

“A letter came by post and Jing had opened it and asked me to ring MidXXXXons and explain to them how I – what I knew, more or less explain what she – how she came into this garment, and because she – well, there was a bit of a language barrier there, and I was Australian, she got me to ring up MidXXXXons...

What did she ask you to say? ... She asked me to say that the – that she saw a customer coming to her showroom with a garment that had a sequins style rib cage shirt or top, and that’s how she became – that’s how she got the design, that she actually took a photo of the garment that the person had on and she sent it over to her manufacturers in China and – to see if they could copy the design without the sequins.”

She then spoke to Mr FeXXr of MidXXXXons in those terms.

In cross-examination, there was something of a suggestion or inference that Ms ToXXy had prepared her evidence in conjunction with MidXXXXons or had otherwise had access to Mr FeXXr’s notes. Ms ToXXy denied these assertions, and in my view, convincingly. She said at

P–84:

I suggest to you that there is a possibility that you may have misunderstood the explanation of events provided by Ms CXX? ... No, not at all.”

You always understood exactly what she was saying? ... That’s right.

“And did she explain to you what happened? ... She had explained to me in past conversations what had happened.

And can I suggest to you that she said words to this effect, “All I did was call the Chinese factory and tell them I want something with a rib cage design as it was very popular at the time. I knew about Sass & Bide’s rib cage design, then the factory sent me a sample and I approved it. I have looked up my records. I received 148 pieces after ordering and sold all of them at $15 a piece. I asked for a recall from other retailers but they have been sold out. I did not make any further order”. Can I suggest to you that she said words to that effect? ... No. She told me that there – a customer had come in to her showroom with a rib cage top on with sequins on it.”

“She can get a point across, if that’s what you’re saying, but it’s not as clear as you and I.

She went on to identify a photograph that Ms CXX showed to her before the letter from MidXXXXons was seen. She confirmed that from the start of her employment, she knew there was a copyright issue going on

(P–88).

It is clear that the date of the photograph to which reference was made was 13 September 2010, and it is also clear that that photograph was annexure P to Ms CXX’s second affidavit (Court Book 09XXS). It is clear that that garment is a different garment and not a copy of the applicant’s Skeletor tank-top.

At P–88, the following exchange took place:

At P–89, Ms ToXXy confirmed that the photograph had been taken and would have been sent to China as she understood it. She said:

“And at that time, did she ever say to you words to the effect, “All I did was call the Chinese factory and tell them I want something with a rib cage design as it was popular at the time?” ... No.”

Counsel for Ms CXX then pressed Ms ToXXy as to whether she had assisted in writing a letter to Mr HaXXXs, Ms CXX’s then solicitor. Initially, Ms ToXXy said she remembered writing a few letters and that she was sure some were to Mr HaXXXs, but could not otherwise remember. She was in due course shown the letter written to

Mr HaXXXs which gave a different explanation as to the events, consistent with the position articulated by Ms CXX and put to Ms ToXXy and denied by her. It is fair to say that Ms ToXXy had obviously forgotten about that letter. The substance of her response was that she was effectively requested by her boss to write the letter in those terms. She was somewhat defensive and self-exculpatory when it was brought to her attention that the terms of the letter to Mr HaXXXs were clearly inconsistent with what Ms ToXXy had said to Mr FeXXr, and indeed what Ms ToXXy said Ms CXX had said to her.

She said at P–91:

“Prior to receiving this letter (the MidXXXXons letter) I was not, to my recollection, aware of the brand LaXXkh. I have, as a result of this proceeding, been made aware that LaXXkh’s office is on Kippax Street, Surry Hills, and is very close to my shop. I was not previously aware of this.”

Ms CXX went on to say:

(a) there were a number of rib-cage designs in the marketplace at that time, such as the one worn by that customer;

(c) I did not get the idea to purchase a rib cage design from their garment.”

Her affidavit went on to set out the conversations she had had with

Ms ToXXy in the terms in which they were put to Ms ToXXy by counsel as I have described previously. At paragraph 16 of exhibit R4, Ms CXX deposed:

“To me, this is just a human’s ribs pattern. I didn’t know this would be so similar to something else. And also, I’ve seen other patterns on the Internet which are very similar to this. That’s why I didn’t think this would be so similar to other products or there would be some issues...this is like a normal image of a human organ. And it contains some popular elements from Sass & Bide, but it’s different to Sass & Bide. That was why I didn’t think there would be some problems.”

She went on to confirm at the same page that she was concerned not to copy Sass & Bide because copying from them, or indeed anyone else, would be likely to create legal difficulties.

Ms CXX denied in terms that she supplied the design to China. She repeated that the design was not printed in the factory but was bought from a design shop around the factory (this being a repetition of the inadmissible hearsay evidence previously referred to).

At P–131 Ms CXX said, once again not responsively to the question put:

“The printing factory has many customers and normally, factories only go to the print factory when there are demands of prints.”

This much is commonsense, it seems to me. Even assuming for the moment, as is not in fact proved by admissible evidence, that the KeXX factory was not in the practice of producing any designs itself, KeXX would only ask for a particular design when demand had already been made for it.

Conclusions about the creation of the false Skeletor tank-top

Counsel for the respondents is correct to submit that there is no direct proof that Ms CXX, or anyone on her behalf, sent to China either an original of the applicant’s top, or a photograph, or a scanned design of it. It would be unusual in the extreme for such evidence to be available in a case of this sort.

Counsel for the respondents is also correct to submit that it is not a matter, as it were, of simply weighing up the various possibilities.

It is, of course, for the applicant to prove its case on the balance of probabilities.

Nonetheless, in the ultimate, I am persuaded that the applicant has indeed proved its case. The following matters lead me to that conclusion. This is a case in which the applicant’s design and garment only came into any kind of public domain in late May 2009. It is expressly accepted by the respondents through their counsel that the design had not been leaked while it was in China. All parties accept, and indeed it is the only probable explanation, that somebody in Australia sent either a copy of the garment and/or a copy of the design in copy-able form to whoever copied it in China.

The only persons who have used the copied design are the respondents. I accept, as I said earlier, the evidence of Ms KiXXton on this point. Further, the only parties’ having any interest in having a copy of the design are the respondents.

The reality is that if one were to accept Ms CXX’s account, there has been an extraordinary series of coincidences. It involves Ms CXX seeing the Skeletor design of Sass & Bide and asking, in a completely unfocused way, for some similar garments.

This request made of one amongst very many factories (according to Ms CXX’s account) in Canton happened to go to a factory which happened to seek a design, apparently without any indication of what sort of design was sought in any detail, from a designer which happened to be in possession of the pirated design of the applicant’s garment.

It ultimately, in my view, beggars commonsense to presuppose that this very precise copy, the design of which was ultimately returned to

Ms CXX in Australia by the factory (note not the designer itself) is just altogether too much of a coincidence.

I am further fortified in this conclusion by the fact that Ms CXX undoubtedly was untruthful when she denied Ms ToXXy’s account of having sent a photograph to China.

Whether or not the photograph sent to China was the one that

Ms ToXXy identified in Court will not be known. As indicated previously, that photograph was plainly not the design of the applicant’s Skeletor tank-top.

What is telling is the credit point upon which it was agreed Ms ToXXy’s evidence was admissible. I do not accept that Ms CXX had difficulties in communicating with Ms ToXXy. Ms ToXXy always understood her.

The version of the conversations between Ms CXX and Ms ToXXy contended for by Ms CXX is radically different to that which Ms ToXXy described. Ms ToXXy stuck convincingly to her denials of Ms CXX’s version of events.

I completely reject the submission of counsel for the respondents that the most likely explanation for Ms ToXXy’s evidence is a misunderstanding. Ms ToXXy did not misunderstand Ms CXX, and

Ms CXX, I regret to say, was untruthful when she denied Ms ToXXy’s account of the events. I have no doubt that Ms CXX had sent a photograph to China and asked for a garment to be produced. That is the version of the events that she told Ms ToXXy, and I accept that it is true.

Whether Ms CXX actually saw a copy of the applicant’s Skeletor tank-top (as indeed she had every opportunity to do at Bondi Beach Shopping Mall or elsewhere) or whether it was brought to her attention by a customer or otherwise, I will never know.

Nonetheless, I am quite satisfied on the evidence as a whole and the inherent probabilities to which the evidence gives rise, that the explanation for the production of the counterfeit garment in China is that Ms CXX obtained a copy of it, whether in garment form and/or in photographic form and/or in the form of some document that was scannable, and forwarded it to China with a request for a counterfeit to be prepared.

I do not know and it is not material whether or not this resulted in a sample or a small number of samples being sent and evaluated by

Ms CXX hanging them up for customers to look at (which she says was her practice in part, at least) or whether the success of the skeleton, the Sass & Bide garment, impelled Ms CXX directly to order the material she did. It is of no moment.

What matters is that the counterfeit garments were produced at the behest of Ms CXX in an intentional copying of the applicant’s work.

Did the respondents know or ought they to have known that this was a counterfeit garment?

In the face of the findings I have already made, it is perfectly clear that Ms CXX knew well that the garments were counterfeit. She caused them to be copied.

I will return to the responsibility of the second respondent when I deal with his respondency generally, but would note that he was not cross-examined, and that he has deposed that he had no running in the day-to-day affairs of the business so far as this aspect of the matter is concerned.

Damages

It seems to be common cause that 123 of the counterfeit garments were sold. As is so commonly the case, there is no direct evidence that any particular person who would have otherwise purchased the applicant’s garment did not do so because of the presence of the respondents’ garment on the marketplace.

It is relevant to note that according to Ms KiXXton, BXhX garments were being sold in the sort of stores which would not normally attract LaXXkh customers. That is because the LaXXkh garments would simply be too expensive for those sorts of stores.

I accept the submissions of counsel for the applicant that these sorts of circumstances give rise to an exercise which of its nature must be imprecise.

In Adidas-Salomon AT v Turner [2003] FCA 421; (2003) 58 IPR 66, Goldberg J said at [5]:

The principle is clear. If the court finds damage has occurred it must do its best to quantify the loss even if a degree of speculation and guess work is involved. Furthermore, if actual damage is suffered, the award must be for more than nominal damages. We should add that we can see no reason why this principle should not apply in cases under the Trade Practices Act as well as in cases at common law. We emphasise, however, that the principle applies only when the court finds that loss or damage has occurred. It is not enough for a plaintiff merely to show wrongful conduct by the defendant.

If a court finds damage has occurred as a result of wrongful conduct that gives rise to a cause of action, it must do its best to quantify the loss, even if a degree of speculation and guesswork is involved.”

The applicant has sought compensatory damages of $1,587.30, calculated as 143 garments multiplied by the applicant’s admitted wholesale profits of $11.10.

That is not a satisfactory outcome. There is no evidence that would support such a conclusion.

Each case must necessarily turn on its own facts. In this case, I am particularly influenced by the fact that the applicant’s target market is different to that of the respondents. It is different both in the sense that the applicant offers a more expensive upmarket product and because they tend to try to sell to a younger woman. The crossover is necessarily, therefore, going to be less, especially when it is borne in mind that the preceding factors also suggest that the products are sold in completely different sorts of shops.

Nonetheless, it is more probable than otherwise to me that given that the number of garments sold was described by Ms KiXXton as substantial in Sydney terms, it is proper to give the applicant some measure of damages in this regard. I will order that the applicant receive $350 being the loss of sales on approximately 30 garments, as being approximately one fifth of those sold by the respondents. It is a completely unsatisfactorily imprecise way of proceeding, but represents the best that I am able to do.

Damages for actual loss and for damage to reputation

As I have earlier indicated, there is no doubt that the applicant has indeed created a brand in the LaXXkh name. I reject the criticisms to the extent that they were pressed by the respondents.

I also accept that the applicant does suffer damage to reputation by the respondents’ conduct.

Ms KiXXton’s evidence, which I have accepted, is that there is a substantial reputation in Australia for its designs in the LaXXkh brand, that it sells only to select boutiques, that the BXhX garment was sold in retail stores which, in at least some instances, were close to the retail stores to which LaXXkh sells, and that it was sold for a substantially lesser price.

The presence of the BXhX garment more probably than otherwise would have some diminishing effect upon the reputation of the applicant’s graphic design which would equally diminish the exclusivity of the applicant’s design and its reputation generally.

While it may be the case that the BXhX garment’s existence, in theory, prevents a repeat of the LaXXkh garment in future ranges, I give no weight to this matter. The reality is that sales of the garment had fallen away, that trends change quickly, and I am not satisfied that the applicant has lost or will lose anything in that regard.

In Review Australia Pty Ltd v New Cover Group Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 1589; (2008) 79 IPR 236 and Review Australia Pty Ltd v Innovative Lifestyle Investments Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 74; (2008) 166 FCR 358, Kenny and Jessup JJ awarded damages for damage to reputation because in each case, they found that there was some probable diminution in the commercial value of the design in respect to future use and would have an adverse effect upon the applicant’s reputation in exclusivity of design. Kenny J awarded damages of $35,000 where the respondent had sold 730 units and Jessup J awarded damages in the sum of $7,500 in respect to the sale of approximately 157 units.

The applicant has set out in its written submissions a number of other cases in which damages for damage to reputation have been awarded, and it will instantly be obvious that each case turns upon its own facts.

Here, in all the circumstances of the case, in my opinion it is proper to quantify those damages at a figure of $10,000.

It should be noted again that at P-78, Ms KiXXton said that the 120 to 150 BXhX garments sold inside Sydney would be a significant number of garments. It would be enough to see a presence in the stores. She herself found it easily.

Given the diminution in price, the more down-market stores in which the respondents’ garment was sold and the damage to exclusivity and the like that the case shows on the evidence, an award of the amount I have indicated is in my view entirely appropriate.

Additional damages

Both parties concede that the Court has power to award additional damages pursuant to s.115 of the Copyright Act 1968 (“the Act”). Section 115(4) sets out a number of non-exhaustive considerations that can be considered.

Here, it is clearly relevant that the infringement was so flagrant. As I have indicated previously, regrettably it is not possible to avoid the conclusion that Ms CXX has not only done what she is accused by the applicant of doing, but has lied about it. She set out on a course of action designed to achieve a commercial advantage in circumstances where she well knew, on her own evidence, that such action might be unlawful. P-128 – “Whatever, what brand it is, direct copying something else would create problem”).

It is equally important to deter similar infringements of copyright. Such a proposition is important but requires no further elaboration.

It is also relevant to consider the benefits obtained by the respondents in this course of conduct. The profit made by the respondents was relatively small assuming a run of about 150 garments, and would not have been colossal even with a rather larger one.

The behaviour of the respondents following the revelation of their conduct was in part to their credit and in part not. The letter written to MeXXrs MidXXXXons was disingenuous, as I find, but at least the respondents took appropriate steps to stop any further sales and to recall garments as soon as practicable.

The respondents’ endeavours to conceal their conduct, including the denials in Court by Ms CXX, do not stand to their credit, but in my view it is inappropriate to punish the respondents, so to speak, twice. The conduct was part and parcel of the proceeding and I have already granted damages for loss to reputation.

In all the circumstances, it seems to me that I should make an additional award in the amount of $30,000 under this heading. This was a flagrant breach of the applicant’s copyright. Such breaches should be discouraged.

The responsibility of the second respondent

It was pressed by the applicant that the second respondent was equally responsible for the conduct of Ms CXX because they were in partnership. No other basis for this outcome was contended for.

In my opinion, there is no question in this case but that the first and second respondents were in partnership, that is to say they were carrying on a business in common with a view for profit (Section 1New South Wales Partnership Act 1892).

In my view, both respondent partners are equally responsible for each other’s conduct. The net effect of sections 10 and 12 of the Partnership Act provides for joint and several liabilities for wrongs committed by a partner acting in the ordinary course of the business of the firm. The scope of the phrase ‘the ordinary business of the firm’ was in my respectful view authoritatively considered by the NSW Court of Appeal in Walker v European Electronics Pty Ltd (in liq) (1990) 23 NSWLR 1. The leading judgment given by Gleeson CJ with whom Mahoney and Meagher JJA agreed traversed the authorities in this area and it is clear in the light of Gleeson CJ’s judgment that I should find that the second respondent should also be liable for the misconduct of Ms CXX, notwithstanding that there is no proof that he was aware of it.

Jones v Dunkel points

I gave a clear indication during the running of the trial about most of the Jones v Dunkel [1959] HCA 8; (1959) 101 CLR 298 (“Jones v Dunkel”) points that the parties sought to raise.

Putting the matter shortly, I was against the applicant’s attempt to create a Jones v Dunkel point from the failure of the respondents to call Ms SuyXX XiXX and Ms BilXXn XiXX. The effect of calling them would have been to embroil them in proceedings in which they were seeking to exonerate the respondents but where they could only do so, in large part, by incriminating themselves. In these circumstances, their failure to be called is scarcely unexplained. I have no doubt they would both have refused to take part.

Likewise, I refuse to draw a Jones v Dunkel point against the respondents for failing to call former employees to buttress their case. Former employees are always a difficult problem for employers. It stands to reason that any sense of obligation that those former employees may have had to their employer, more commonly than otherwise, dissipates to the point of extinction when the employment ceases. I do not regard the failure to call them as giving rise to any adverse inference.

Finally, I take an even dimmer view of the respondents’ effort to create a Jones v Dunkel point over the alleged failure of the applicant to conduct its own investigations in China. If ever there was an evidentiary bridge too far, this is it.

The order to be made

I do not think it is appropriate to make declarations in this case. They will add nothing to the outcome. The reasons for the Court’s orders will be clear from the orders themselves and from these Reasons for Judgment.

I do not think it is appropriate to make the injunctive orders sought because the respondents have already returned all infringing garments to the applicant. Injunctions made in these terms would amount in substance to doing no more than requiring the respondents to obey the law and that is not a proper purpose for injunctive relief.

Accordingly, there will be orders requiring the respondents to pay the applicant damages for damage to reputation and additional damages pursuant to s.115 of the Act.

The respondents will pay the applicant’s costs of the proceeding. In the circumstances of this case and the particular complexities it gave rise to, in my view, these should be taxed in default of agreement on the FeXXral Court Scale.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and sixty-one (161) paragraphs are a true copy of the reasons for judgment of Burchardt FM

Date: 3 November 2010

1300 91 66 77

1300 91 66 77

HOME

HOME