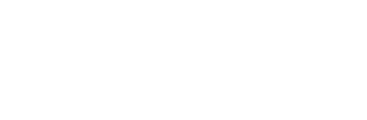

【Classic Cases】ChXXg v WX [2010] NSWCA 1X

IN THE SUPREME COURT

OF NEW SOUTH WALES

COURT OF APPEAL

CA 29XX11/09

SC 2XX9/07

MACFARLAN JA

YOUNG JA

HANDLEY AJA

Tuesday 2 March 2010

CHXXG v WX

Judgment

1 MACFARLAN JA: These proceedings arose out of the payment of in excess of A$5,000,000 by the appellant to his sister who was the first defendant in the proceedings but is not a party to this appeal. The funds were transferred in the period 2001 to 2005 from China, where the appellant was resident, to Sydney, where the first defendant was resident. The appellant alleged that the first defendant did not deal with the funds in accordance with his directions and successfully sought various personal and proprietary remedies against her. It was common ground between the parties to the proceedings that the funds were not transferred to the first defendant beneficially and that she therefore held them on trust for the appellant. There is no appeal from the orders made at first instance in relation to the first defendant and her property.

2 A substantial portion of the funds received by the first defendant from the appellant was paid by her during the period 2002 to 2004 to her now estranged husband, the respondent. She gave evidence that she believed that the respondent was engaged in a steel import/export business, that the appellant was in some way supporting or assisting the respondent in this business and that the payments by her to the respondent accorded with the appellant’s instructions. The appellant denied giving any authority for funds to be paid to the respondent and sought personal and proprietary remedies against the respondent in respect of the funds paid to him. The appellant was unsuccessful at first instance in his attempts to trace the funds, either at common law or in equity, into the hands of the respondent. He does not appeal against the findings on his tracing claims.

3 The appellant was also unsuccessful in his common law claim against the respondent for moneys had and received. The rejection of this claim is the subject of this appeal. The respondent accepts that if the appeal is successful, there should be judgments against him in favour of the appellant in the amounts of A$2,653,091 and US$229,949.

The primary judge’s holdings as to legal principles

4 In reliance upon the decision of the House of Lords in Lipkin Gorman (a firm) v Karpnale Ltd [1991] 2 AC 548 (in particular the speech of Lord Goff at 572), the primary judge found that “[i]t is now established that a remedy for moneys had and received will lie against a third party recipient of funds paid by the plaintiff to the second party, in circumstances which would give the plaintiff a restitutionary claim against the second party, so long as the third party is not a bona fide purchaser for value without notice” (Judgment [32]). He held that this was so whether or not the property received remained in existence in the hands of the third party recipient. Neither of these propositions has been challenged on appeal. Accordingly, it is unnecessary to consider their correctness in light of the matters discussed in Heperu Pty Ltd v Belle [2009] NSWCA 252; (2009) 258 ALR 727, particularly at [144] – [145] and [150] – [162].

5 His Honour then held that proof of a change of position “solely in reliance on the security of the payment” was, in principle, a defence available to the third party recipient of such funds and that the onus of proof of such change of position rested upon that recipient. Again, neither of these propositions is challenged on the present appeal and it is unnecessary to consider their correctness.

The primary judge’s factual findings

6 On the claims against the first defendant, the primary judge preferred the evidence of the appellant to that of the first defendant and found that the funds paid to the first defendant were not dealt with in accordance with the appellant’s directions. On the claims against the respondent, the judge accepted, contrary to the first defendant’s evidence, that the funds given by her to the respondent were given to him for the purpose of him gambling. The respondent did this, at the Star City Casino in Sydney and the Crown Casino in Melbourne, and to a significant extent lost the funds he received. His evidence was that he returned winnings and any unused amounts to the first defendant. This was denied by the first defendant.

7 The judge’s conclusions as to the availability to the respondent of the change of position defence were expressed as follows:

“35 It is clear enough that the expenditure in question here – namely, [the respondent’s] gambling expenditure – would not, and indeed could not, have been undertaken, but for the payments in question. In my view, a relevant change in position, sufficient to bring the facts within the defence, is established.

36 However, the defence of change of position is available only to those who act in good faith, that is, in the sense of an actual belief in the security of the receipt [Lipkin Gorman v Karpnale

, 579-580]. Although the second defendant said that at first he assumed that the funds came from his wife, he admitted that at some stage he became aware that she was using funds obtained from her brother. [The respondent] was asked (T216.46):

Q. In addition to the other monies that you got from your wife, you knew that your wife did not have from her own sources this amount of money to give you; didn’t you?

A. INTERPRETER: I didn’t know in the beginning.Q. You found out at some stage that this wasn’t your wife’s money; didn’t you?

A. INTERPRETER: Yes she told me later that some of the money was from her brother.Q. When did she tell you that?

A. INTERPRETER: I can’t remember; maybe in 2005 or 2006.

37 None of the relevant advances to [the respondent] were made in 2005 or 2006; the latest transfer of funds to him the subject of the claim, was on 1 April 2004, being item 43 in the Second Schedule in the Amended Statement of Claim. None of the transactions described in Exhibit PX08 were in 2005 or 2006. In those circumstances, I must conclude that [the respondent] has changed his position on the faith of the payments to him, and that a restitutionary remedy for moneys had and received is not available against him.”

8 In dealing with the appellant’s tracing claim against the respondent (which is not in issue on the appeal), the judge had said:

“31 For the purposes of establishing an equitable proprietary remedy, a plaintiff must also establish that assets still exist to which that remedy can attach. The plaintiff has failed to do so. To the contrary, the evidence suggests that the funds no longer exist in [the respondent’s] hands. It is true that [the respondent] gave evidence that he had returned the funds, to the extent that they were not lost, to [the first defendant], who had placed them in a cardboard box in her factory; but even if this uncorroborated and improbable story were true, it would not establish that there were traceable funds in [the respondent’s] hands. Accordingly, an equitable proprietary tracing remedy is not available.”

Issues on the appeal

9 The issues on the appeal are narrow ones related to the availability to the respondent of the defence of change of position. They are reflected in the two grounds of appeal which were pressed. These grounds alleged that the judge erred in that he:

“2. Did not find that the Respondent failed to prove a change of position in circumstances where his Honour rejected the Respondent’s evidence that the winnings from the gambling were placed in a cardboard box in [the first defendant’s] company’s factory and where the Respondent did not otherwise explain what had happened to the winnings from the gambling.

3. Failed to find that the Respondent knew or ought to have known that the monies gambled by the Respondent were those of the Appellant.”

Proof of change of position

10 The effect of the appellant’s argument in support of ground 2 of the Notice of Appeal was that, by the fourth sentence of paragraph [31] of his Judgment (quoted in [8] above), the primary judge rejected the respondent’s evidence that he returned to the appellant the winnings and unused amounts from his gambling activities and that the judge should in those circumstances have found that the respondent had not made out his change of position defence because he had not explained what had become of a substantial part of the funds he had received. It was implicit in the argument that because the respondent also did not prove what amount of the funds had been lost in gambling, his defence should be rejected in toto.

11 This argument raised the question of whether the judge did in fact reject that evidence of the respondent.

12 The appellant relied in this respect on the phrase “if this uncorroborated and improbable story were true” used by the judge (see [31] of the Judgment quoted in [8] above). The appellant contended that “the story” there referred to by the judge was not simply the evidence to which the judge referred in that sentence of money being placed in a cardboard box in the first defendant’s factory but the more general evidence, also referred to by the judge in that sentence, that the respondent had returned the funds which had not been lost to the first defendant.

13 The comments of his Honour are open to more than one interpretation but if his judgment is read as a whole, I consider that it is tolerably clear that his Honour did not intend to reject the respondent’s general evidence as to return to the first defendant of funds constituting winnings and unused amounts.

14 First, whilst one can understand why the judge may have regarded the placing of what may have been hundreds of thousands of dollars in a cardboard box in the factory as “improbable”, the same cannot be said of the respondent’s evidence as to return of winnings and unused amounts. Accepting that on a number of occasions over a period of time the first defendant gave the respondent money with which to gamble and that they were living together at the time, it is not inherently improbable that the winnings and unused amounts with which the respondent returned from the casinos were given back to the first defendant.

15 Secondly, I consider that acceptance of the respondent’s evidence as to return of the winnings and unused amounts to the first defendant is implicit in the judge’s finding that a relevant change in position had been established.

16 His Honour was clearly familiar with the decision in Lipkin Gorman as he referred to it and relied in his judgment upon particular pages in it. In that case a claim for money had and received was made against a gambling casino operator which was the innocent recipient of stolen money which had been used to gamble at its premises. Central to the decision was the finding by the House of Lords that any change of position by the casino operator was to be measured not by adding up the payments made by it back to the fraudulent person from whom it had received money in the course of his gambling activities but by taking the net balance of the winning and losing bets placed by that person. Bearing in mind this principle, of which the judge must be taken to have been aware, his Honour’s finding that the change of position defence was made out necessarily involved his acceptance of the respondent’s evidence that he returned any winnings and any unused amounts to the first defendant. If his Honour had been of the view that whilst the respondent had proved that he had lost substantial funds in gambling he had not proved what had become of his winnings and unused amounts, his Honour would have rejected the change of position defence at least in part and probably, because the amount lost in gambling had not been proved, in toto. If (as I believe the judge must have considered) the funds were either lost by the respondent in gambling or returned by him to the first defendant, a relevant change of position had been proved as to the whole of the funds received by the respondent and it was unnecessary for the respondent to prove which amounts were parted with by him in which way.

17 The brevity of the judge’s reasoning in connection with the change of position defence is accounted for by the brevity of the submissions that were made to him on the defence. There were no written submissions put before the judge and it does not appear that the oral submissions were transcribed. Whilst senior counsel for the appellant has informed this Court that he put to the judge at the hearing a general submission that the evidence of the respondent should be rejected, there does not appear to have been any specific submission that if the respondent’s evidence generally were accepted, and that of the first defendant rejected (as occurred), nevertheless the reverse should occur in relation to the specific issue of whether the gambling winnings and unused amounts were returned by the respondent to the first defendant. It is not surprising in these circumstances that the judge did not explicitly deal with that point, particularly when the first defendant denied any knowledge at all of use of the funds for gambling. Moreover, whilst there was exploration in the respondent’s cross-examination of his evidence as to the return of his winnings and unused amounts to the first defendant, it was not expressly put to him in cross-examination either that his evidence as to that matter was false or that he had used or applied the winnings in some way other than by return to the first defendant. The latter was of particular importance in light of the fact that the evidence made clear that the respondent no longer had any of the funds which had been paid to him by the first defendant.

18 In these circumstances I consider that the foundation for the appeal on this ground (that the judge rejected the respondent’s evidence of return of the winnings and unused amounts to the first defendant) has not been made good. Accordingly, this ground of appeal must fail.

19 I would add that the appellant did to some extent travel outside the boundaries of the ground of appeal to refer to evidence which it was suggested on his behalf indicated that the winnings and unused amounts were not returned to the first defendant. The submissions did not however reveal any basis upon which the appellant could, consistently with the principles stated in Fox v Percy [2003] HCA 22; (2003) 214 CLR 118, overturn the judge’s credit based finding on this issue.

The knowledge of the respondent

20 The appellant further contended that the respondent had not shown that he was unaware that the funds he received came indirectly from the appellant (and by inference, that they did so without the appellant’s authority). It was argued on his behalf that the evidence relied upon by the judge in relation to his finding in favour of the respondent on this issue (see [36] and [37] of the Judgment quoted in [7] above) was insufficient in circumstances where the respondent would have known that the first defendant would not have been able to provide the funds from her own resources.

21 Again, the hurdle identified in Fox v Percy relevant to an attack on a credit based finding has not been surmounted. For such an attack to succeed it is necessary to show that the finding is contrary to “incontrovertible facts or uncontested testimony”, “glaringly improbable” or “contrary to compelling inferences” (Fox v Percy at [28] – [29]). The evidence relied upon by the appellant (principally to the effect that the business conducted by the first defendant was “earning not much at all”) does not assist the appellant in light of the existence of evidence before the judge, from the respondent, that the first defendant told the respondent before they were married in 2002 that she had over $2,000,000 of her own money and evidence before the judge that the first defendant herself gambled with significant amounts of money at the Star City Casino.

22 Accordingly, the second ground of appeal which was pressed fails also.

Orders

23 As the appellant has failed to make good either of his grounds of appeal, the appeal should be dismissed with costs.

24 YOUNG JA: As Macfarlan JA has set out the facts and circumstances, there is no call for me to repeat them.

25 The only point in this appeal is whether the respondent had made out his defence of change of position to the appellant’s restitutionary claim.

26 In the instant case, neither party challenges the propositions that the defence is available to the respondent if he has discharged his onus of showing that he changed his position “solely in reliance on the security of the payment” of the relevant monies to him by his wife.

27 A complication in this case is that the money was paid to the respondent and representations made to him about the payment on which the respondent says he relied, not by the appellant, but by the wife. There was dispute as to what the wife said at the time of payment. Whatever she said, it was not authorised by the appellant.

28 This raised the possibility that the respondent’s reliance was not a result of the inducement of the appellant: see State Bank of New South Wales v Swiss Bank Corporation (1995) 39 NSWLR 350. However when the possible significance of the fact that payment was made by the wife was put to counsel, he chose not to argue this point, so that I can pass on.

29 The notice of appeal set out three grounds of appeal. Ground 1 was that the primary judge allegedly erred in finding that the respondent had established a change of position by gambling away the monies which had been paid to him by his wife.

30 Whilst that ground might appear to open up an examination of the whole of the evidentiary material, that was not the way the appeal proceeded. In answer to the presiding judge, appellant’s counsel said that what he wished to put under ground 1 was encapsulated in ground 2 so that ground 1 was not pressed independently of ground 2.

31 Appellant’s counsel conceded that had the respondent merely said that he lost the money gambling relying on the fact that he could use the money to gamble, the defence would have been made out. However, counsel submitted that the respondent went further and the judge did not accept that further material. Thus, the submission went, as the judge did not accept the respondent as a witness of truth, the respondent had not discharged his onus. However, the matter is not that simple.

32 The case is a little unsatisfactory in that we were told that the main thrust of the case below was on matters other than change of position. Thus, it would seem little attention was given to the matter in addresses and the ex tempore judgment only deals briefly with it. However, there is no complaint made as to the adequacy of the primary judge’s reasons though there is debate as to their construction.

33 It is important to realize that this appeal is not one calling for an essay on the law of restitution. Indeed it does not even call for a review of all the evidence before the primary judge to ascertain whether or not the judge erred in finding that the respondent had discharged the onus on him of proving the defence. The challenge is solely based on the two grounds referred to in the reasons of Macfarlan JA.

34 On these grounds, all I need say is that I agree with his Honour’s impeccable analysis.

35 Accordingly I would agree that the appeal should be dismissed with costs.

36 HANDLEY AJA: I agree with Macfarlan JA.

**********

04/03/2010 -- Grammatical error - Paragraph(s) [6]

17/03/2010 -- Case name and citation omitted. - Paragraph(s) Coversheet

1300 91 66 77

1300 91 66 77

HOME

HOME